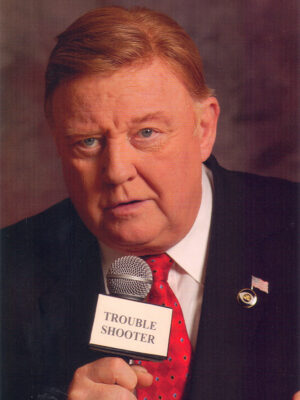

Judd McIlvain

Radio, Television, Internet Broadcaster

Degree(s): BJ '65

An Early Start in Broadcasting

Judd McIlvain, BJ ’65, has been in radio and TV for 45 years. He was first on TV when he was 12 years old and hosted a show called “Children’s Digest.” The show, sponsored by Blue Star Potato Chips of Chicago was 15 minutes long on WBLN-TV in Bloomington, Ill. McIlvain did radio shows as a disc jockey in Columbia, Mo., at radio stations KBIA and KFRU when he was 15 and 16 years of age.

At 17, he produced and hosted a television show called “Dance Party” at the Jefferson City, Mo., KRCG-TV station. Teenagers from area schools would come to the studios each week and dance to rock ‘n’ roll on television. The show was sponsored by Pepsi Cola and was 90 minutes long. McIlvain was the first TV producer to fight for African-American teenagers to dance on a so-called white TV show and win. A week later, the Ku Klux Klan showed up at the studios and demanded that the white teenagers not dance on the show if black teenagers were permitted to dance. It was 1959, and the white kids danced with white kids and the black kids danced with black kids, but for some members of the community, that was too much integration. Pepsi did not give in and cancel the show, and it continued until the end of the 13-week contract. However, McIlvain had to have one show with black dancers and one show with white dancers. Therefore, on the black show, he was the first white host of a black dance party TV show. After the 13-week contract, and many protests from the Klan, the show was not renewed.

After high school McIlvain joined the National Guard and immediately went on active duty with the U.S. Army. He graduated as a military police officer, served out his active duty and then returned to serve four years active reserve. McIlvain was one of the youngest military police to reach the rank of sergeant.

He worked part time in radio and TV news reporting when he went to the University of Missouri School of Journalism. During his college studies, McIlvain studied a summer semester in Monterrey, Mexico, where he learned Spanish.

A Career in Television and Radio

After getting his Bachelor of Journalism (BJ) in 1965, McIlvain headed for Central America to be a freelance news reporter. If there was a riot or a small war, he was there covering it and trying to find customers in the United States who would take his stories. McIlvain did some live feeds for ABC News from the riots in Panama City in 1965. He was paid $20 per radio story. While working for United Press International (UPI), McIlvain was arrested in Venezuela for taking pictures of the secret police beating demonstrators and of the trial of dictator Perez Jimenez. McIlvain was released on bond, and UPI’s bureau chief suggested it would be a great idea for him to flee the country because the penalty he was facing was six years in jail. McIlvain took the advice and was out of Venezuela the next morning. He has not been back since.

McIlvain has worked at eight different TV stations throughout the country.

He worked at the CBS-TV affiliate in Houston for 18 years. He was the assignment editor/ producer, general reporter and investigative reporter.

In 1986, Rupert Murdoch, the owner of FOX-TV, brought McIlvain to Los Angeles, Calif., to be the Troubleshooter on the FOX station, KTTV.

In 1988, he was hired by KCBS-TV in Los Angeles and moved his Troubleshooter operation to CBS, where he worked for 10 years.

McIlvain has done stories on CBS’ 48 Hours with Dan Rather, with whom he worked in Houston, Texas, in the late 1960s. McIlvain also helped produce stories for Geraldo Rivera at ABC’s 20/20. He was often on Geraldo’s syndicated show until the fighting and chair throwing began.

McIlvain has won two L.A. Emmys, eight Golden Mikes and four L.A. Press Club awards for outstanding TV reporting. One was for outstanding reporting during the Los Angeles riots. He also received Texas’ highest award for investigative reporting, the Headliners Award.

McIlvain now has a website, www.troubleshooterjudd.com, and he also hosts an Internet consumer action radio talk show on www.adviceradio.com.

McIlvain and his wife Linda have been married for 40 years and have three children, Aaron, Sean and Marisol. They live in Woodland Hills, Calif.

J-School Reunion Under Gunfire

By Judd McIlvain, BJ ’65

It was one of those cold January mornings in Columbia, Mo., when you cannot see the sun, and the sky looks like it will be producing snow at any moment. The temperature was about 38 degrees, and there was a prediction of possible snow, if a front that was moving on Kansas City continued on to Columbia.

I was standing outside of Neff Hall on Ninth Street, saying to myself, “Is that all there is?” I was graduating from the J-School at midterm in January 1965, and it had just been explained to me that there would be no ceremony or even a certificate until June. A nice clerk wished me congratulations saying, “You now have a BJ degree from the University of Missouri,” and then she quickly took a phone call.

So here I stood on Ninth Street, the strollway in Columbia, a BJ graduate with no job and no one to tell that I had finally made it through J-School. I walked across the street to the Heidelberg Inn to get some hot coffee and think about the fact that I now had a BJ, and I was a journalist without a job.

I was sitting at the bar that was empty, with the exception of the bartender who was setting up for the day. In walked another student who sat on a stool near me. I decided I had to tell someone I had finally graduated from J-School. So I introduced myself and told this complete stranger that I was now a grad. He was surprised and said, “You are not going to believe this, but I just graduated and got my BJ today at midterm.” His name was Carlos, and he was from Venezuela. We had never met during all our time in J-School.

I said, “Let me buy you a drink,” so we toasted our joint graduation from the University of Missouri. He told me he was going home to Caracas, Venezuela, to work for an English language newspaper there. I told him I was headed to Central America to start my career as a foreign correspondent, but I did not have a job yet. He wished me luck, and I wished him luck, and I left the Heidelberg to walk to my car.

During that cold walk, I kept thinking of what Dr. Edward Lambert, the head of the Radio and TV Department at J-School, had told me. He had counseled me to forget the idea of heading for Central and South America to work as a foreign correspondent and take a job at a small radio station in Southern Missouri to get experience. Well, I cashed in a small insurance policy, took my $500 and headed for Central America by train.

Now, flash forward two-and-a-half months, and I was working part time for United Press International in Caracas, Venezuela. When I arrived in Caracas I was broke, and I made the rounds of news operations to see if I could get a job. Reuters had an opening for a reporter, and since I spoke both English and Spanish and had a BJ degree, I thought I would have it made. But the people at Reuters said they only hired reporters who spoke at least five languages. I didn’t know anyone in the country who spoke five languages. By the way, they never did find a reporter who spoke five languages, and they ended up closing the news bureau. Finally I got four hours of work each day at UPI, translating Spanish news stories into English for the afternoon New York feed. UPI also used me on photo assignments, and I was paid $25 per picture that they used on the wire. One morning I was sent to a small demonstration and possible riot in downtown Caracas.

Of course, I was hoping it would be a big riot so that I could get several pictures that UPI would buy for the New York wire and I would made $25 each. I was extremely poor at the time, and I needed the money just to eat. (Small sidebar: I found a little hot dog stand near the UPI bureau, and they sold good hot dogs for 12 cents. This stand was my lunch and dinner wagon – that is, until a kid told me that the hot dogs were really made out of dog meat.)

At the small riot, I was right up front in the crowd to get good pictures of the cops and the protesting people. There was a construction site on two corners, and the crowd had the cops surrounded. The rioters started throwing bricks and concrete from the construction sites at the cops. I was shooting picture after picture until the cops pulled out their guns and started shooting directly into the crowd where I was standing. It was a stampede of people. You could hear bullets whistling down the cannons of tall buildings. There were also the screams of the wounded. Being a U.S. Military veteran, I was running a zigzag path trying to keep from being hit. I was looking for quick cover so I could continue shooting pictures. There was a bobtail truck with a lift on the tailgate that was raised, so I ducked under it for cover. About a minute later, another man ducked under the lift, and the bullets were still whizzing by the truck. I looked at him, and he looked at me with a surprised expression. I said, “Aren’t you the guy I bought a drink for at the Heidelberg across from J-School about two months ago?” He said, “Yes, I’m Carlos.” (This was a real WOW journalism moment!) Thousands of miles from Columbia, Mo., and months since our toast at the Heidelberg Inn, we were both working journalists and ducked under the same truck for cover.

Now, who says J-School grads never get together after they leave Columbia? I never saw Carlos again, and within two weeks I was arrested by Venezuela’s federal police for taking pictures of another demonstration. The government cancelled my work permit and charged me with being an illegal alien working in Venezuela. I was released that evening to UPI, and the bureau chief suggested I flee the country. I did, with the police one step behind me.

Those are the facts, Dr. Lambert, just the facts, and I know this would not have happened in southern Missouri. However, I did escape from Venezuela. That’s a story for another day, but thank goodness for a U.S. oil industry family who hid me from the police.

Updated: November 9, 2011