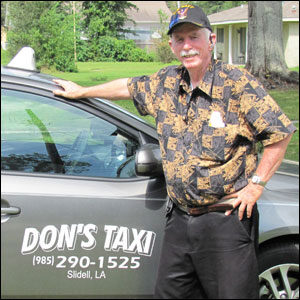

Don Wells

Cabbie/Journalist at Don's Taxi

Degree(s): BJ '68

Whereabouts: United States, Slidell, Louisiana

The last time Don Wells, BJ ’68, got fired from a newspaper job, he decided to take his act on the road. Literally.

It was 1975, and after working in advertising sales at a number of West Coast papers, Wells found himself at the Fairfield (Calif.) Daily Republic. He had a major disagreement with his supervisor and got fired. So he chucked traditional journalism and became a cab driver.

“I got tired of getting fired or quitting in disgust and newspapers going belly-up on me,” says Wells. “I needed a job bad, so I answered an ad in Palo Alto (Calif.) for a cab company.”

For 30-plus years now, Wells has been driving a cab in cities all around the country, from northern California to southern Louisiana. He writes about and photographs his passengers and surroundings for publication.

That’s how his unusual career as a cab-driving journalist was born.

A Humble Beginning

Wells was born in a log cabin in Jesup, Ga., a rural area in the southeastern section of the state. He became interested in photography as a child and dreamed of taking pictures for Life magazine. The original plan was that he would earn his degree in photojournalism at the Missouri School of Journalism before joining the publication’s staff. But Wells’ education was put on hold when he felt the call to join the military. Wells wanted to do his part for his country when the U.S. and the Soviet Union came dangerously close to nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.

Military Experience

Wells at this time was a resident of Tennessee and took the state’s “Volunteer” nickname to heart. He signed up for the Navy and got his choice of assignments. Flying airplanes appealed to Wells’ sense of adventure, and he earned his wings and commission at the age of 20. Wells learned to fly the highest-technology aircraft of the time, serving two tours of duty in the Navy in the late 1950s, flying AD-Skyraider dive bombers off of aircraft carriers, mostly off the coast of China.

In 1962, tensions between the U.S. and Cuba came to a head when the Soviet Union began installing ballistic missile bases in Cuba, just 90 miles off the coast of Florida. The threat of a nuclear confrontation had never been higher, and Wells extended his military status.

“I became a weekend warrior at Bennett Field on Long Island, N.Y.,” says Wells. “I was in the pipeline to crank out naval aviators, and the fleet was going to need plenty of fliers.”

Wells then volunteered at a base near Pensacola, Fla., where he trained naval aviators in T-28 Trojan airplanes.

Wells at the Missouri School of Journalism

Wells finally began his studies at the Missouri School of Journalism. He quickly embraced the truth, fierce independence and a dedication to professionalism embodied in The Journalist’s Creed. The principles became a part of his soul, he says, but the creed did little for his classroom performance. Wells admits he was a poor student.

“I was flunking out of school, because I just wasn’t getting it,” he says. “All of the different categories of photography and news did not have any meaning to me.”

Wells also had different political views than many of his professors. He identifies himself as a “Tea Party kind of guy” and thought his teachers were too liberal. But, he still respected them. Two of his favorites professors were John Merrill and Cliff Edom. Edom was “the Vince Lombardi of photojournalism,” he says, referring to the famous coach of the Green Bay Packers. He and Edom butted heads occasionally as both were stubborn as mules,” Wells says.

Ultimately Wells did manage to graduate.

“I just crossed the finish line, is about all I did,” Wells says. “I got a degree and just started jumping up and down.”

Wells thought his career would follow the familiar path of his classmates: Get a job and move up the ladder. That was not to be the case for Wells.

“I see it like show-biz,” he says. “You slug away for years, and maybe you make the big time. I never left the minor leagues.

Wells became “The Midnight Cabbie,” but his devotion to journalism never waned. His spirit of independence and his love of journalism resulted in numerous freelance newspaper columns in the “Gonzo” journalism genre, epitomized by Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe.

Wells became “The Midnight Cabbie,” but his devotion to journalism never waned. His spirit of independence and his love of journalism resulted in numerous freelance newspaper columns in the “Gonzo” journalism genre, epitomized by Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe.

Wells says his experience driving a cab allows him to appreciate the richness of life.

“I’m out here on the street taking the pulse of what’s going on,” says Wells. “It’s the invigorating experience of now.”

That reality included Wells’ living in his car for 11 years when he started out.

“The rent was right,” he says with a chuckle.

Wells would sleep while parked behind the local Denny’s or in church parking lots. He made deals with motel managers in the cities in which he worked. They would allow him to shower in rooms that had been vacated but not yet cleaned by the staff. Wells experienced a wide range of circumstances and tries to incorporate his appreciation for the human condition in his work, he says.

Observer of Life

Wells, now in his 70s, still drives his cab for 12-14 hours per day, finding stories and photo-ops as he works.

His publications include “The Midnight Cabby,” “Search for Truth” and “The Anatomy of a Robbery.” The last one was written as the result of Wells being robbed in his taxi. Twice.

In 1976, while driving his cab in San Francisco, his passenger robbed him at gunpoint. Wells survived the incident but was shaken. He used his journalism training to interview a local psychologist to find out the best way to react to a robbery situation, and based “The Anatomy of a Robbery” on that conversation.

Twenty years later, Wells credits this book – “The Anatomy of a Robbery” – for saving his life again when he found himself staring down the barrel of a chrome-plated handgun in San Jose.

Twenty years later, Wells credits this book [“The Anatomy of a Robbery” ] for saving his life again when he found himself staring down the barrel of a chrome-plated handgun in San Jose.

“I used the information in my own booklet to walk away from the ordeal,” he says.

The culprit was later convicted of a four-year string of cab robberies, which included the murder of one driver.

The threat didn’t deter Wells’ love of driving his cab, and he shows no sign of slowing down. Wells loves to interact with people and hear their stories. Some of these make their way into his writing and photographs.

Don the Cabbie Tells Stories

Wells’ says that one of his favorite memories is recounted in his essay “Six Pennies and a Nickel.” One night he drove a woman from her job at a residence in one of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods to her home in one of the poorest. Wells’ journalistic instincts took over, and he asked her about her thoughts on discrimination. Her answer stunned Wells as it focused on God, love and the purpose of life.

When she got out of Wells’ cab, she tipped him six pennies and a nickel, giving him her last 11 cents.

Random Violence

Another time in Reno, Nev., someone shot a bullet through Wells’ cab, nearly killing the young woman who was his passenger. Later, as Wells sat in a diner having coffee, he told the story to the waitress. She was upset; Wells was nonchalant.

“I’m sorry,” Wells said. “I didn’t mean to scare you. It’s no big thing.”

“Well, it does scare me, and it is a big thing,” she said.

The police told Wells that they would probably never find the shooter. Wells wasn’t surprised or angry. He says that’s just an occupational hazard of being a nighttime cab driver. His philosophy is to “keep on working, keep on loving, keep on,” he says.

Worries About the Future of Journalism

Wells’ customers often complain about the current state of reporting, he says, although he never mentions to his passengers that he is, at heart, a journalist.

A strict adherence to Walter Williams’ Journalist’s Creed has stuck with Wells through the years, and are evident in his writing. His four favorite words – “truth,” and “accuracy, accuracy, accuracy” – have taken him on an adventure of a lifetime.

“These people bristle at what they read and see,” Wells says. “I have a concern that we’re losing our credibility.”

But, Wells’ experience at the Missouri School of Journalism convinces him that all is not lost.

“It gave me the tools to do what I do,” speaking of his education and his devotion to the creed.

Wells doesn’t try to hide his pride in graduating from the J-School.

“Every so often, my thoughts wander back to my old Alma Mater, the University of Missouri, back to the green, green, grass of a Missouri summer, back to the portraits on the walls of the journalism greats,” he says. “Did I really graduate from you, the finest and largest journalism school in the world? I did.”

A strict adherence to Walter Williams’ Journalist’s Creed has stuck with Wells through the years, and are evident in his writing. His four favorite words — “truth,” and “accuracy, accuracy, accuracy” – have taken him on an adventure of a lifetime.

Dan Claxton is working on his master’s degree in journalism. Originally from Springfield, Mo., Claxton worked in the radio industry for nearly 30 years and served as news director at six Missouri radio stations before returning to school. He earned his bachelor’s degree from MU.

Updated: December 12, 2011