Fred Bruning

Managing Editor, Columnist, Professor (Retired)

Degree(s): BJ '64

Whereabouts: United States, Huntington, New York

Fred Bruning, BJ ’64, often told his Stony Brook University students of the influential mentors, peers and teaching style that inspired him during his time at the Missouri School of Journalism and who shaped him into journalist he is today. Bruning’s professors taught the importance of deadlines and the ethical implications involved.

“We must be as fair and accurate as we can be,” Bruning told his students. “We have to serve this noble mission of public service to our country.”

His passion for journalism and the role it plays in our democracy was prevalent throughout his career as both a writer and professor.

Bruning’s dream of becoming a writer at a “big time” publication took him to Newsday for 30 years in three tours of employment. He travelled around the country and occasionally overseas. He reported on 9/11, the anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination and a journalist-turned-murderer.

“Writing was just about the only thing I was somewhat good at,” the Brooklyn, New York, native says.

After high school, Bruning studied at the University of Denver and, after two years, transferred to the Missouri School of Journalism.

A Missouri Journalism Education

Bruning says his choice to study at the Missouri School of Journalism was one of the most important ones he made during his journalistic career. He speaks of mentors G. Thomas Duffy and Donald Romero who taught him real-world reporting, the pressures of deadlines and correct grammar.

Duffy taught news writing and was night city editor for the Columbia Missourian. He was a legend to the many future journalists he influenced and shaped. The School has a faculty endowment in Duffy’s name.

Bruning describes Duffy as a “no-nonsense, crusty city editor type who taught us what journalism was all about.”

In 1963, Bruning experienced Duffy’s methods firsthand during a controversial story when he was assigned to cover a speech given by a member of the university’s athletic department. Bruning remembers the speaker making a comment with racial implications and being told by the speaker, “Now, I don’t want to see anything about this in the paper tomorrow!”

Upon returning to the Missourian newsroom, Duffy said, “Just give me your notes.” Duffy wrote the story to be printed the next day,” Bruning recalls. “This was so typical of Duffy, who was not going to be turned around by anybody, and it was a thrilling moment as a student.”

One of the shifts at the Missourian was called nightside and involved covering various meetings and breaking news. Duffy was running the operation.

Once, Bruning, and another nightside reporter, Kent Bernhard, were assigned to cover a fire in Moberly, Missouri, roughly 40 miles from Columbia. There was little time to write the article upon their return.

“When we came back that evening, Duffy was waiting for us to start the story,” Bruning says. “We only had a few minutes to put together a piece. As I remember, we squeaked in just under deadline to make the next morning’s paper.”

This was a priceless piece of his education as he learned the importance of deadlines, and it gave him an edge over others who were entering the industry.

Another mentor, Professor Donald Romero, an accomplished New York Magazine writer during the 1950s, stressed the importance of style and grammar. Today, the School’s Don Romero Prize acknowledges Romero’s encouragement and contribution of outstanding magazine journalism. It is awarded to a student who exemplifies exceptional magazine writing capabilities.

“Romero was my idea of a ‘New York writer’: suave, worldly, sophisticated in all ways, but terrifically down to earth,” Bruning says.

One of Bruning’s most memorable grammar lessons from Romero was learning on the importance of being alert for dangling participles. Years later, while working at Newsday, Bruning spotted a dangling participle in the first paragraph of a new novel by the esteemed 20th century author, Norman Mailer.

“I got a short feature out of Mailer’s miscue,” Bruning says. “Romero should have shared the byline with me.”

Learning the Role of Journalism

Upon graduation, Bruning applied to many jobs before accepting a reporting job at the Colorado Springs Free Press. The editors at the paper were so excited to have a Missouri graduate that they paid him more than they had ever paid a beginning reporter: $90 a week in January 1964.

“They told me they never had a Missouri student before and were obviously thrilled,” Bruning says. “I learned a lot there, but it took me a while to understand how important the job of the reporter was and how it is linked so significantly to the democratic system.”

Bruning’s experience in Colorado Springs was bittersweet, and he decided to leave six months after starting his position. He moved around for the next several years in order to find a workplace he was passionate about.

“You have to keep in mind there was a tradition of reporters moving,” Bruning says. “You grab your clips, you parlay those clips and leverage what you think is a slightly better job, and so on until you get the one you want. At some point, you hope, or many of us hope, that you will end up at one of the big newspapers.”

His hope of a job at a major newspaper was achieved when he was offered a position at the Miami Herald. “It started to dawn on me that this is a very serious job, and I had to pay very close attention to my work,” Bruning says.

Bruning’s career led him to many publications, which included Newsweek. In its heyday, the weekly publication was read in the White House and was considered a top-of-the-line magazine.

“I learned to be a better writer there,” Bruning says of his three years at Newsweek.

From there, Bruning would spend most of his career at the Long Island-based newspaper Newsday, where, in three tours of duty, he was a reporter for nearly 30 years.

Life at Newsday

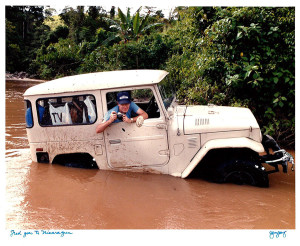

Bruning mostly wrote feature stories during his time at Newsday, highlights of which include a retrospective of John F. Kennedy during an anniversary of his 1963 assassination, a story on a controversial AIDS case in rural Michigan, and a feature about Benjamin Linder, an American volunteer who became the only American to die in the Contra War in Nicaragua in the 1980s.

Bruning also has covered many iconic events in the nation’s history. After 9/11, he was based in New York City for several months, walking through the remains of the World Trade Center to collect information for stories. He also wrote about Ronald Reagan’s funeral.

Bruning wrote one of most important stories of his career about reporter-turned-criminal Ron Porambo. “He was a unique journalistic character,” Bruning says. “He worked at many papers but died at the New Jersey State Prison convicted of murder.”

While working on a 30-year retrospective of a folk singing group from the civil rights era, Bruning faced an ethical dilemma. One member of the trio had been convicted of a sexual offense involving a minor. The incident was widely report at the time and Bruning felt it deserved at least a mention in any piece tracing the history of the group.

“In one final interview, I asked the man about the incident,” Bruning says. “He became very upset and could not understand why I would bring this up 30 years later. It happened so long ago, and he didn’t want attention brought to the issue.”

Bruning went to his editor about what to do regarding the situation. His editor said he could include it if he felt it necessary. Staying true to his responsibilities as a journalist, Bruning put it in the story.

“It was a long story, 3,000 or 4,000 words,” Bruning says, “I put it deep in the article and mentioned the conviction.” Bruning would use that experience as a lesson in his future classes.

“I often bring this up while teaching ethics. If you write a 3,000-word story and don’t even mention it, someone is bound to ask why,” Bruning says.

While working at Newsday, Bruning accepted a position at Stony Brook University. He incorporated much of what he learned from his Missouri journalism professors, especially Duffy, into his classroom.

Bruning shares many other stories from his career while teaching his students about ethics. He says even though the industry is changing, ethical considerations stay the same and are not complicated.

“You don’t make things up, and you check things the best that you can,” Bruning says. “You talk to as many people as time allows on stories, simple or complicated, and you present it as honestly and with as much fairness to every side – not just two sides.”

He taught his students that although the media landscape is more diverse with social media and the Internet, ethical principles remain constant.

“It is still the same ethic,” Bruning says. “Get it right, be fair, write it so people can understand it and step back. Nobody cares what you think about it. Let the public make up their own minds. Give them the raw materials in an even-handed fashion and then move onto the next story.”

Teaching the Role of Journalism

Although Bruning says his students thought he was demanding, assigned too much work and was uncompromising, he doesn’t think he was unreasonable.

“I like to be thought of this way, though, because you have to impose a newsroom standard even in the classroom because there is no point in fooling around about it,” Bruning says.

His experience at the Missouri School of Journalism draws a direct line between his teaching at Stony Brook as a professor. He loves to be known as passionate about journalism because that is how he viewed the teachers who inspired him during his time at the School.

“I expect the work to be as close to perfect as you can get it every time out, because if people won’t read it, why write it in the first place?” Bruning says. “It must be perfect because of the importance of the press.”

After all, Bruning believes journalists have a special duty to the public.

“We are on a mission here, and it is a noble,” Bruning tells his students, noting, “even though people dislike the press and see all kinds of nefarious motivations, we have to keep our heads up and do our jobs.”

Bruning emphasizes the importance of the First Amendment in every class.

“Not every country has the kind of press freedom that we do. I think that we are among the guardians of liberty,” Bruning says. “If you don’t have a vibrant, unfettered free press, you can’t have the kind of country that is a true democracy.”

Taking a Step Back

In 2015, Bruning turned 75. He says that at his age, working 10 to 12 hours a day (after editing student’s papers and preparing for class) seemed exhausting. So after approximately 20 years of teaching at Stony Brook, he retired. Fall 2015 was Bruning’s first semester not teaching.

He still writes occasional columns for Newsday and serves as managing editor of the Graphic Communicator, a quarterly publication serving the unionized print industry.

“These two amount to nearly a full-time job,” Bruning says. “I do miss the students, the intellectual give and take, and the high that teaching always provides.”

Bruning hopes that all of his past students and all who are interested in journalism remember that there are all kinds of unusual opportunities through the online world.

“Remember that journalism is not going to go away. Whatever shape or form it takes, wherever people read the news, it is going to continue,” Bruning says. “There is no way for it to disappear.”

About the Author: Anna Weiss, a strategic communication senior from St. Louis, will graduate in May 2016. She has interned at Captive Minds in London and Provision Living Senior Communities in St. Louis. Weiss plans to volunteer and travel abroad a for two months after graduation and then land a job in the public relations field in a large metropolitan city.

Graduate student Kiara Ealy contributed to the development of this story.

Updated: December 18, 2015