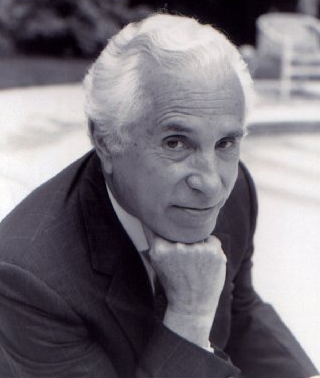

Seymour Topping

Former Foreign Correspondent, Foreign Editor, Managing Editor and Director of Regional Newspapers at The New York Times (Retired)

Degree(s): BJ '43

Whereabouts: United States, Scarsdale, New York

If journalists write the first draft of history, as has been claimed, it is a draft dictated by war. Centuries of “journalists,” from ancient historians such as Herodotus to modern 20th century reporters, have documented the rise and fall of civilizations marked by winners and losers of war. Their stories have shaped the historical eras we know today.

Such a historical legacy, however, did not inspire Seymour Topping, BJ ’43, as he prepared to write his first account of the Chinese Civil War in 1946. A young Army officer during World War II with a yet unused journalism degree from the Missouri School of Journalism, Topping relied on the inspiration of Eugene Sharp, long-time Columbia Missourian city editor.

“The first time that I sat down to write a dispatch on the (Chinese) civil war, the only professional experience that I’d had was at the Columbia Missourian,” Topping said on a visit to the School. “The teacher I recall most of all was Gene Sharp, and so I’ve always felt a sense of gratitude to him and to the School of Journalism for training me for my first job in journalism.”

The rest, they say, is history.

Literally, in Topping’s case. Topping went on to become one of the most renowned foreign correspondents in the latter-half of the century, covering several of history’s notable conflicts – the Chinese Civil War, French Indochina War, our Vietnam War and much of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. He moved through the ranks of the International News Service, the Associated Press and finally the New York Times, where he spent more than 30 years and retired as editorial director for the Times’ 32 regional newspapers.

Throughout a life and career dominated by war, “Top,” as he is called by those closest to him, has depended on several important factors to reach his goals – his family, friends, mentors, memories and his Missouri School of Journalism training. Topping made many sacrifices in order to have the career he wanted, but as his story shows, it was also a life of great gain.

War Losses and Gains

Sitting on top of the mantel in Topping’s New York office is a black and white photograph of Omar Akins, Topping’s closest friend at the University of Missouri. They lived in the same boarding house near campus and shared similar experiences as young collegians in the early 1940s – mandatory ROTC training, occasional trips to the Shack for a beer and service in World War II.

They were both called up for service at the same time – Topping to the Army, Akins to the Air Force. Not long after, Topping received devastating news; Akins had been killed in a training crash.

“I think of him more than anyone else,” Topping said, recalling the memory some 60 years later.

For this reason, Topping’s first stop when visiting campus over the years has been Memorial Union, where Akins’ name and those of other companions lost in the war are inscribed in the white stone tower.

“Coming back after an absence of more than a decade has been a very moving, somewhat emotional experience, because I recall the friendships I’ve had here, the faculty who were my mentors and also both the academic and social life,” Topping said.

Topping’s Missouri years and those immediately following were a time of loss because of the war but also of great gain. Ironically, the same war that took his best friend would be the starting point for his career as a foreign correspondent – the goal that originally brought him to the Missouri School of Journalism.

A Goal-Oriented Youth

From the age of 16, when Topping was the editor of his high school newspaper in New York City, he knew he wanted to be a journalist. But he didn’t want to be just a regular reporter; he specifically wanted to be a foreign correspondent in China. Topping was inspired by Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China, a seminal book on the beginning of China’s Communist Party. Snow, from Kansas City, briefly attended the Missouri School of Journalism prior to his 13 years reporting from China.

With such a specific goal, Topping said the Missouri School of Journalism was a “natural choice.”

“I knew that Missouri had special connections with Asia, particularly with China and Japan. Dean (Walter) Williams had traveled extensively to China and was instrumental in the establishment of schools of journalism in Shanghai at St. John’s and at Yenching University in Peking,” Topping said. “Also, there were quite a number of correspondents working in Asia who were graduates of Missouri’s School of Journalism.”

Another far less commonly cited attraction was the School’s location.

“As a New Yorker, I wanted to familiarize myself more with the Midwest and other parts of the United States,” Topping said.

That familiarization process proved to be a bit more challenging than expected. One of Topping’s most vivid memories is of his first encounter with horses at mandatory ROTC, which at the time was still using horse-drawn field artillery.

“I’d never been on a horse,” Topping said. “I remember going into the stables with the other students – friends of mine – most were Missouri farm boys. They collapsed in laughter when I tried to get on the horse from the wrong side.”

Like the many other challenges he would face in his career, Topping approached this one with a determination to master it. He practiced riding everyday in the stables and eventually made Missouri’s polo squad. The team’s coach, Lt. Leslie Green, never let Topping forget that incident, always labeling him “the New York boy who came to Missouri and learned to ride a horse.”

One could argue that Topping learned more at Missouri than how to ride a horse. He still credits his experience covering general beats at the Columbia Missourian with jumpstarting his reporting career. In addition Sharp’s mentoring, Topping also received guidance from Frank L. Martin, the second dean of the School.

“He was particularly influential in the practical work that I did at the Missourian. He was truly an outstanding and inspirational teacher,” Topping said.

Topping’s time at the School was cut short, however, when his ROTC class was called up for duty several months before graduation. Having completed the necessary credits, Topping did receive his degree, but it came in the mail instead of at a graduation ceremony. It was the first of Topping’s many life and career events that would be affected by war.

Life Abroad

By 1946, Topping had served for three years as an Army infantry officer. With World War II over, many of his fellow officers were returning home. Topping, however, who was then stationed on Leyte in the Philippines, began positioning himself for the career in China he’d always wanted. As luck would have it, Topping, at an officer’s club on leave in Manila, ran into an old friend – Ernie Ernst, MU grad and former captain of the polo team. Ernst was headed home and offered Topping his job on Luzon at Camp John Hay (an American base) as liaison officer with the nearby city of Baguio, the summer capital of the Philippines.

“The importance of that – besides the fact that I was glad to leave the jungles of Leyte – was that while in Baguio, I came into contact with the newspapermen in Manila,” Topping said. “It was through those journalists that I was able to get a job as a stringer for the International News Service in Peking, now Beijing. I flew from Manila to Peking in November 1946 and went to work covering the Chinese Civil War. I was given the pretentious title of ‘Chief Correspondent for North China and Manchuria.’ My salary was $50 a month plus space.”

At the time, Peking was the center for covering the brutal war in North China and Manchuria between the armies of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Tze-tung’s Communist Party. In 1947 INS transferred Topping, promoting him to a staff member in Nanking, the Nationalist capital; but after six months he switched to the AP and a much better paying job. It turned out to be a smart move. Topping said he scored his “greatest beat” in China reporting the fall of Nanking in 1949 to the Communists.

In the midst of war, Topping achieved more than just career success. In Nanking, he met his wife, Audrey Ronning, who was the daughter of a Canadian diplomat and was attending Nanking University. Audrey was evacuated with her mother and siblings with other diplomatic families when the Communists approached the city. Topping and Audrey were engaged at the time and eventually married in Canada when Topping returned home on leave. They returned to Asia together.

Over the next few decades, the Toppings would canvas the globe together on journalistic assignments. Audrey became a widely published photojournalist and the mother of five daughters, whose birthplaces mirror Topping’s reporting assignments: one born in Saigon, two in London, one in Berlin and one in Scarsdale, N.Y., where the Toppings live today.

In February 1950, when Topping opened the AP bureau in Saigon for coverage of the French Indochina War, he became the first American correspondent to be stationed in Indochina after World War II. After two years in Indochina, he went to London where he covered the diplomatic beat and then on to divided Berlin in 1956 as bureau chief. Topping returned to the United States in 1959 to go to work for The New York Times. A year later, the Times sent him to Moscow as chief correspondent, where he reported on the first space shots, De-Stalinization and the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Times sent him back to Asia in 1963 as chief correspondent for Southeast Asia. He was based in Hong Kong but spent most of his time covering the wars in Indochina.

A Historical Legacy

With 20 years of experience as a foreign correspondent, Topping settled in New York in 1966 as the Times’ foreign editor. He spent the next 27 years rising through the ranks of management, serving 10 of those years as managing editor of The New York Times. Returning to Missouri periodically over the years, Topping is especially proud of two visits: one in 1968 to receive the Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism, and the other in 1982 to speak at the School’s commencement. Finally, he was able to participate in the ceremony denied to him by World War II. He received further recognition in 2000 when Topping and his wife, Audrey, received the first Greenway-Winship Award from the International Center for Journalists for their roles in international journalism.

Topping retired from The Times in 1992 as editorial director of the company’s regional papers in order to become Administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes at Columbia University’s School of Journalism. During his nine years as Administrator, he also originated and taught a course on “Covering Regional and Ethnic Conflicts.” After retiring from Columbia University in 2002, Topping conducted a master’s seminar on “The Evolution of the Media and the Public Interest – History and Issues” in Columbia’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

During more than half a century of service to journalism, both as a correspondent and an editor, Topping covered nearly every major event that has shaped post World War II history.

“The events that I covered on the ground in Asia were critical to American society,” Topping recalled. “The Chinese Civil War and early conflicts in Vietnam, which led on into the Korean War, the struggle with the Soviet Union for Berlin – all impacted deeply on the future of the American people.”

Topping has continued to write and lecture at Columbia University, at other venues in the United States, and at universities in China. He is the president of the International Advisory Board at Tsinghua University in Beijing. In March 2010 he published his latest memoir: On the Front Lines of the Cold War, An American Correspondent’s Journal from the Chinese Civil War to the Cuban Missile Crisis and Vietnam. The book relates his experiences on the ground in covering the major events of that era. His other books are: Journey Between Two Chinas (1972), The Peking Letter, A Novel of the Chinese Civil War, and Fatal Crossroads, A Novel of Vietnam 1945.

Topping said that although today’s war reporting from Iraq is strikingly different with embedded journalists and intense television news coverage, the conflict itself can be compared politically and culturally with the roots of the wars he covered in China and Vietnam. He said that it is essential that generations of aspiring journalists should know that history to understand what is transpiring today; but they must also understand what working as a journalist entails, Topping added.

“They (students) should only go into journalism if they’re prepared to make a real commitment. I always tell people who put that question to me, ‘If you don’t have a fire in the belly, don’t do it,'” Topping said. “Don’t go into journalism because it is such a demanding profession in both the professional and the personal sense. It calls upon you to make all kinds of sacrifices in your personal life. But having said that, in return, you have very rewarding experiences, and you also have a lot of fun.”

Topping made that commitment to journalism from the day of his first report on the Chinese Civil War, when he relied upon the training given to him by his mentor Gene Sharp and the Missouri School of Journalism. That cub reporter may not have realized the implications of his commitment in 1946, but the veteran journalist does now. The sacrifice of a journalist pays off when one’s life work becomes a part of the enduring legacy of history.

Updated: November 11, 2011