Steve Woodward

CEO at Nozzl Real-Time Technologies Inc.

Degree(s): MA '79

Whereabouts: United States, Portland, Oregon

Early Interest in Writing

Woodward was interested in writing at a young age. As a child, he enjoyed writing stories and papers for school. He got involved with his high school’s newspaper and decided to stay in Dayton for college. Woodward attended Wright State University, a public university of 18,000 students that offers both undergraduate and graduate degree programs.

“I got an English degree at Wright State after trying about 15 different majors, but I really wanted to be a writer,” Woodward says. “I thought maybe I’d become a great American novelist.”

While attending Wright State, Woodward wrote for the university’s campus newspaper, The Guardian. He also wrote feature articles for the Wayne Chronicle, a small local paper serving the suburbs north of Dayton.

After receiving his bachelor’s degree, Woodward worked at the public relations department at Wright State for two years. His position required him to work with other journalists, and he became increasingly interested in reporting.

“I decided that the reporters I was working with were having a lot more fun than I was,” Woodward says. “That’s what struck a chord with me.”

“We loved the paper [Columbia Missourian] so much that we were simply there anytime we weren’t in class or cramming for tests.”

Woodward also had a lifelong fascination with science, particularly astronomy and physics. A mentor at Wright State suggested that he merge his interests in science and writing to become a science writer. He began considering graduate school, to learn more about how to build a career by combining his passions for writing with that of science.

“I’ve always been interested in writing,” Woodward says. “I thought that reporting was the way to at least make a living out of writing.”

Woodward looked into Columbia University, Northwestern University and the University of Missouri as options for graduate school. He knew that Missouri had an excellent journalism school, and he found out that the school also offered a great science-writing program.

“Mizzou’s science-writing program was a strong attraction for me,” Woodward says. “At that point, it became a no-brainer.”

Woodward had never been to Columbia before, but he decided that the opportunity to explore two of his passions at a school with a solid reputation was too good to pass up. He chose to pursue his master’s degree at the Missouri School of Journalism.

“I came sight unseen and knew absolutely no one who had graduated,” Woodward says. “It was absolutely a leap of faith.”

Expanding Horizons

Woodward didn’t know anyone when he arrived on campus, but he didn’t intend to keep it that way. Right away, he set out to make the most of his time at Missouri and take advantage of the many opportunities available.

“I decided when I came to Mizzou that I was going to take advantage of my time there and stop spending all my time worrying about getting straight A’s, as I had all my academic life,” Woodward says. “I took a couple of courses outside of journalism, both as an intellectual challenge and to learn more about the subjects I was interested in.”

For Woodward, this philosophy extended beyond the Journalism School. He took a beginner’s adult swim class through Columbia Parks and Recreation to overcome his fear of water. He auditioned for a school theatre production, “Marat-Sade,” a play about the Marquis de Sade. He had always wanted to try out for a play during high school but was too reserved.

Woodward, a self-proclaimed shy person, was also attracted to journalism in part because he thought it would force him to meet people. Woodward soon realized that many longtime established journalists who he came in contact with at the J-School were also shy. One reporter in particular from the New York Times talked about being a shy person when he came to speak at the J-School, and he made an impression on Woodward.

“That was a revelation for me…I thought wow, this is really cool, you can be a journalist and shy at the same time,” Woodward says.

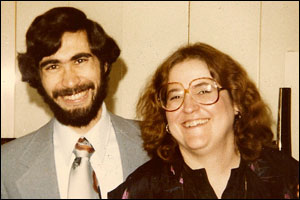

Being shy didn’t inhibit Woodward from making an especially important connection at the Journalism School. He met his wife, Sandy Richardson (now Sandy Woodward), a broadcast news major, in an advertising class on the first day of school. At the time, an advertising class was required for all news editorial-track students in the J-School. Woodward recalls that many editorial students weren’t always happy about having to take an advertising course. However, he and his friends reluctantly admitted that they knew that advertising was an important part of the journalism industry, providing much of the funding for the papers they wanted to write for some day.

“There was one professor who would drive everyone crazy because she would always say, ‘If it weren’t for advertising, we’d all be meeting in a phone booth,'” Woodward says.

Woodward remembers that the advertising class often required students to complete layouts for print grocery ads in the hour-long class.

“I would drive my wife nuts because she would be frantically moving all of the chickens next to the turkeys, all of the vegetables together,” Woodward says. “I would just sit there and think for 50 minutes, and in a flurry of activity in the last 10 minutes, I’d move everything around and be done.”

Woodward took Sandy on their first date the night after his audition for “Marat-Sade.”

“The director asked all of us hopefuls to demonstrate a human emotion. I was at somewhat of a loss, so I decided on the spur of the moment on anger,” Woodward says. “The only thing I could think to do was punch the pillar in the middle of the room as hard as I could.”

After the audition, Woodward got back to the Tiger Hotel where he lived at the time and realized that his right hand was broken.

“That night, I went out to dinner with Sandy, and I ate with my left hand. Afterward, I asked her if she could drive me to the ER at University Hospital, which she kindly did,” Woodward says. “My right hand and forearm were in a cast for the rest of the semester, so I had to take notes and write papers with my left hand. My right still doesn’t lie flat.”

Woodward was learning to come out of his shell, take risks and pursue a variety of interests. Later, his willingness to take risks would prove to be an important part of his career.

Learning from the Best

While pursuing his love interest, Woodward also pursued his love of writing. He was hired as a teaching assistant at the Columbia Missourian.

He was interested in copyediting and started off working at the copy desk for Brian Brooks, then the professor in charge of the copyediting sequence. Later, Woodward moved to the city desk and worked for professor George Kennedy, then the Missourian’s city editor.

Woodward says that Brooks and Kennedy were the two biggest influences on his education, as he worked most directly with them. He also enjoyed working with Dale Spencer, who taught journalism law, and Daryl Moen, the managing editor of the Missourian at the time. Woodward says that he might not have realized it at the time, but today he truly appreciates that he got opportunity to learn from such knowledgeable and talented journalists.

“To be able to work with the high-level, talented faculty who worked there was just amazing,” Woodward says. “George Kennedy had come from the Miami Herald. It would have taken me forever to work with a guy like that if I had entered the workforce from ground zero. I learned so much from those people. People who are good investigative reporters, great editors, they’re all there at the Missouri School of Journalism. Availing yourself of their knowledge and talent is an incredible opportunity.”

Life at the Missourian

In addition to the knowledge he gained from faculty members, Woodward is certain that the Missouri Method of learning-by-doing prepared him for a career in the journalism industry. The hands-on experience he gained cultivated his passion for journalism. When Woodward entered MU, he was wanted to pursue a career in the journalism industry simply because he was interested in writing. However, working at the Missourian helped him realize that he wanted to become a reporter because he enjoyed learning about the variety of topics he covered in his stories.

“I left Mizzou wanting to be a reporter because I found that it was fascinating to learn about stuff,” Woodward says. “I really like reporting, finding out information and the presentation of information.”

Woodward fondly remembers dedicating much of his time during school to the Missourian.

“There must have been a weekly schedule, but no one followed it,” Woodward says. “We loved the paper so much that we were simply there anytime we weren’t in class or cramming for tests. We’d start the day with endless pots of coffee at IHOP, wander over to the Missourian and close down the Heidelberg at the end of the day.”

Woodward feels that the Missourian was the perfect laboratory and Columbia was the perfect setting to foster reporting and copyediting skills that he could use in his career. He appreciates the fact that he learned to write about local city and government issues while working at the student-staffed newspaper, as this was important in the early years of his career.

“I know that if I had gone to Columbia University, for instance, that I would’ve been able to go cover the U.N.,” Woodward says. “But, the reality is that when people go out into the real world of journalism, they aren’t covering the U.N., they’re covering their local city governments.”

Woodward recalls a particularly strange event he experienced at the Missourian, as he worked during the “Year of Three Popes” in 1978. Late in the night of Aug. 6, after preparing the latest edition of the paper for press, he and another teaching assistant were winding down at the Heidelberg and just as the bar was closing down and the lights were coming on, someone from the Missourian suddenly ran in yelling, “The pope died!” Woodward and his friend quickly ran back to the newsroom to tear up and make a new front page about Pope Paul VI’s death. Just 33 short days later, once again, Woodward was unwinding at the Heidelberg near closing time when the news reached him that the successor, Pope John Paul I, also died unexpectedly.

“Someone ran in saying, ‘The pope died again!’ and we had to run back to the Missourian again,” Woodward says. “It was really bizarre. That’s a big memory, being blinded by the Heidelberg lights with somebody yelling, ‘The pope died again!'”

While working at the Missourian, Woodward learned an important lesson about not taking anything for granted. During a night of boredom at the newspaper’s city desk, Woodward decided to play a gag on the copy editors. He added a number of ridiculous, bizarre headlines to the feature article preview section of the front page and sent it to the copy desk.

“I thought I was just going to be funny and throw in off the wall, couldn’t-possibly-be-true items,” Woodward says. “I sent it over to the copy desk. Later, I went over to the back shop and noticed that these things were actually on the page, ready to go to the press! I just totally freaked out that everyone took it seriously.”

After the incident, Woodward knew he would never do anything like that again. He learned that even if you make up a ridiculous story, there’s always that someone is going to believe that it’s true. He knew that in order to become a successful journalist, he would need to protect his credibility by carefully exercising his power to be a believable reporter.

“Even today, I’m still sort of shaken by even thinking that might’ve gone to the press,” Woodward says.

Technology at the School has come a long way since Woodward worked at the Missourian. The paper was using terminals that were hooked to central minicomputers at the time. Woodward remembers that a thunderstorm knocked out the electricity one night, so the staff had to prepare the paper with ticker tape, by running stories on long strips on paper. The strips had punch-hole patterns on them that corresponded to letters of the alphabet that were run through a machine that set type.

“I just remember running out the strips, writing down which story was on the strip, tying a rubber band around it and hanging it on a hook until we needed it,” Woodward says. “It was pretty exciting that night.”

Transitioning to a Career

Woodward participated in the Washington reporting program. The experience was beneficial in helping him develop skills that he would use in his career. Woodward says that a major reason why the Washington reporting program was so great was because of Steve Weinberg, the professor who directed the program at the time.

“He was a terrific teacher, so I learned a lot about covering the federal bureaucracy,” Woodward says. “He taught me that there were 1,400 reporters covering the White House, but only three people working on the rest of the federal government, where all of the actual work was going on.”

While participating in the program, Woodward’s major project was creating a guide to public documents at the Securities and Exchange Commission, which regulates the stock exchanges. The research he did for his project actually led to him writing one of the biggest stories that broke while he was at his first job with the Kansas City Star.

Woodward indirectly used the “Mizzou Mafia,” the network of Missouri Journalism alumni working in the industry, to land his job at the Kansas City Star. City editor David Zeeck, BJ ’73, hired Woodward as a reporter. While working at the Star, Woodward participated in coverage of the 1981 Kansas City Hyatt Regency Hotel skywalk collapse. A skywalk tragically collasped during a tea dance, killing 114 people and injuring 216 others. The Star hired a structural engineer to investigate the situation, who revealed that there had been a significant change from the original design of the walkways. This discovery later led to a lawsuit and large award to victims and their families and earned the Star staff a Pulitzer Prize for local news coverage.

Woodward worked at the Kansas City Star for three years. He spent a year covering Kansas City’s northern suburbs, a year covering city hall and a year covering science and medicine. Then, the founding editor of the Kansas City Business Journal, Don Keough, recruited Woodward to be a part of the start-up team of the new publication.

Founded in 1982, the Kansas City Business Journal became the first in a chain of business publications now called the American City Business Journals. Keough had been a political reporter for the Columbia Tribune when Woodward was at Missouri. Although they never met, Woodward considered Keough to be the best local politics reporter he’d ever read.

Woodward had never considered business journalism before, but he joined the publication because he was excited about the opportunity to work with Keough. He says that his biggest fear in joining the publication was that business reporting was going to be boring. However, Woodward figured out that if he looked beyond the corporate façade to uncover what was going on behind the scenes of the industry, business reporting could be very interesting. Before he knew it, he was uncovering a world of intrigue including murder-for-hire schemes and hot money.

“What appealed to me was that it had all the elements of great literature: money, power, and greed,” Woodward says. “There’s drama that goes on that doesn’t get into mainstream papers usually, but it sure got into the business journals.”

Woodward’s experience at the Kansas City Business Journal got him excited about business reporting, and led to him working in the American City Business Journal chain for a number of years. The company sent him to Portland to start-up with Portland Business Journal in 1984, when he was just 29. While there, he was promoted to general manager and in charge of all departments of the paper. In 1987, Don Keough passed down the editor position at the San Francisco Business Times, founded one year earlier, to Woodward.

Following his time in San Francisco, Woodward returned to Portland to work at the Oregonian. Portland became home for his family, as he reported and edited for the paper for 20 years. During his time at the Oregonian, Woodward ran into the Mizzou Mafia once again. He believes that at the time, there were around 11 Missouri graduates working there.

Woodward still occasionally runs into other Missouri alumni in the industry today.

“It’s always great, because we share common stories,” Woodward says.

Changing Times

While at the Oregonian, Woodward saw the Internet change the journalism industry. Initially, he noticed that newsrooms became much quieter, as reporters were doing much of their background research and even some of their interviews online instead of over the phone. As newspapers began to move online, Woodward saw many journalists becoming worried that the Internet would eventually push newspapers out of business. However, Woodward saw the Internet as an opportunity, not a threat.

“Throughout the whole newspaper industry, the whining became deafening,” Woodward says. “I just thought, come on, quit whining, grab the Internet as an opportunity and figure out how to turn it to your advantage.”

“What we want to do is really expand the content so that we have everything from the Emmys to Justin Bieber’s haircut,” Woodward says. “We’re going to build a stream on everything, because everybody, I figure, has a news sweet spot. Everyone is obsessed with something. Because of our ability to build an infinite number of streams, there will be a stream for everybody.”

Woodward knew that if newspapers were going to stay afloat, they would need to branch out of their old modes of thinking. Newspapers seemed to perceive the Internet as competition, rather than a tool to expand their readership. He felt that newspapers were always a little behind the times when it came to technology and moving their content online. He decided that he wanted to do something about this, and began brainstorming ways that the Oregonian could be doing things differently.

After accepting two-year buyout from the Oregonian in 2008, Woodward began doing research to come up with a method of changing the way that people consume news. Eventually, a colleague who also had left the Oregonian approached Woodward. The colleague was interested in figuring out a way to extract public records and display them online. He introduced Woodward to a software developer who was working on a micro-blogging project. Together, the three began discussing how to combine their ideas.

“It occurred to me that if you took the one guy’s idea about extracting public records and the other guy’s micro-blogging project, you could move public records out of databases and flow them on a Twitter-like stream,” Woodward says. “Maybe you would have something there.”

As their discussions continued, the idea expanded far beyond public records. They began looking into Twitter, blogs and newsfeeds. Essentially, they began coming up with a way to aggregate news content and move it in a real-time, Twitter-like stream.

This initial idea evolved into what is now Nozzl.com, an Internet news service that aggregates online content including news, social media, local content and public records and streams it to Web browsers in real-time. Nozzl.com users are able to choose a headline and immediately view a constantly changing stream of the story as it appears on different news and social media sites. Woodward and his team are developing mobile technology and perfecting the site with the ultimate goal of providing users with a way to stay updated and never miss information about any topic that interests them.

“Now, what we have is essentially a way to grab any kind of online content, not just public records, but anything in the online universe,” Woodward says. “The content has really exploded beyond what we imagined originally.”

“What we want to do is really expand the content so that we have everything from the Emmys to Justin Bieber’s haircut,” Woodward says. “We’re going to build a stream on everything, because everybody, I figure, has a news sweet spot. Everyone is obsessed with something. Because of our ability to build an infinite number of streams, there will be a stream for everybody.”

Woodward wants to continue to expand Nozzl Real Time Technologies Inc., in hopes that Nozzl.com and real-time streaming technology will fill a much-needed niche in the journalism industry. He hopes that his site will introduce a new way for journalism to be delivered.

“With the business journals, it was fun because we kind of changed the way that America did business journalism,” Woodward says. “This time, we get a chance to again change the way that journalism is done, which is very cool. That’s really my goal here.”

Updated: November 15, 2011