Timothy Blair

BlairPR (Retired)

Degree(s): BJ '73

Whereabouts: United States, Bel-Air, California

It was the nationwide HIV and AIDS epidemic that shaped Timothy Blair, BJ ’73, both personally and professionally.

In the early-1990s, Blair was working in healthcare public relations in Los Angeles. The HIV and AIDS epidemic was sweeping the nation. Most Americans had heard about it, but few knew much more.

The gay community, however, knew everything about it. Thousands had died and many more were infected. Facts about the disease – what caused it, why people got it and how to treat it – were on-going topics in the brave new world of the emerging 24-hour news cycle.

Yet, speculation continued. It was fueled by the public’s fears and on-going ignorance. It took the deaths of sons, brothers, friends, neighbors, nephews, cousins and fathers to put a face on the epidemic. Only then did the perceptions of the public and the government’s public health policies begin to change.

“We wouldn’t know about gay people if not for AIDS,” Blair says. “The government wasn’t talking about it; it was the journalists.”

Blair used the skills he learned at the Missouri School of Journalism to help people understand what was happening. His degree and family heritage would motivate him to do great things.

Born Into a Legacy

Blair was born into a journalism legacy. His grandfather, Clay Cowgill Blair, was the president and publisher of the Joplin Globe in Missouri. Blair started helping at the age of seven and was a copy boy by 15, running typed stories from one section of the newspaper office to the other. His aunt, Rebekah (Blair) Hughes, worked at the Globe and married Fred Hughes, who later became president of the paper.

“There is such a thing as printer’s ink, as we had it running through our veins,” Blair says.

Blair was a reporter for the Parkwood High School newspaper for two years and helped produce the school’s radio show. In 1985, Parkwood and Memorial high schools consolidated to form Joplin High School, and the newspaper was renamed the Spyglass.

Blair followed his family’s tradition by attending the University of Missouri. Seven generations of Blairs have attended the university, and four have done so with a degree from the School of Journalism.

“Everyone went to school at the University of Missouri,” Blair says. “It was hallowed ground. I don’t think there was ever a question of what I would do after high school because it was if it had already been decided.”

MU: Where the Blairs Get Degrees

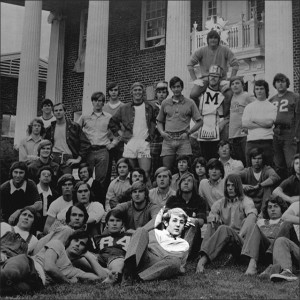

When Blair stepped on the MU campus in the fall of 1969, he continued in the footsteps of his father, uncle, grandfather, great uncle, and great grandfather by pledging the Sigma Nu fraternity. The Rho chapter was the second secret society to be established at the university and has remained on campus for 129 years. Blair lived in the chapter house during his time as a member, which is the same house members live in today.

The family legacy continued to be apparent in Blair’s classes as well. Professors and administrators recognized him as a member of his family, who had a long history of public service. His grandfather won the Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism in 1960 and was a member of the University of Missouri System Board of Curators.

“His picture hung on the back wall of Neff Auditorium,” Blair says. “They had pictures of several alumni and his picture was on that wall. So every class I took in that hall, my grandfather was looking over my shoulder.”

Blair’s maternal family, the Harris family, was one of the founding families of Boone County and the University of Missouri. John Woods Harris, Blair’s great great grandfather, is remembered for his public service to the community and as a member of the University of Missouri Board of Curators in the late-1800s. He served on the first State Board of Agriculture and later became president. Woods Harris helped establish what is now the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources at the university, and later received an honorary master’s degree from the college.

Blair’s great uncle, Morris Harris, graduated from the university and was chief of the Associated Press News Bureau in Tokyo and Shanghai prior to World War II. He became a prisoner of the Japanese for over two months, along with three other MU graduates. Their coverage of the rise of communism in China gave Westerners a broader perspective. It was a story that was widely known by faculty at the School of Journalism.

Blair paved his own path in the family legacy when he decided to pursue advertising rather than the news-editorial track at the School of Journalism.

“At the time, advertising is really what I wanted to do because there was a romance associated with it,” Blair says. “What drew me to public relations was that it was a hybrid of advertising and news.”

“It was understood that advertising had a deep tradition in journalism,” Blair says. “Walter Williams, founder of the MU School of Journalism, talked about the profession of advertising as very much a part of the principles and ethics of journalism.”

Advertising students had the opportunity to meet alumni working at advertising agencies across the country. Blair and five other students were chosen to work as interns for the Advertising Age Awards in Chicago. At the time, all students took courses in news and advertising as part of their studies. This included a course that involved working at the Columbia Missourian. Professors expected advertising students to be able to write well, and the Missourian provided them with opportunity to harness those skills.

“I attribute the success I have achieved as a public relations practitioner to my experience of working as a journalist,” Blair says. “Knowing how journalists do their jobs and understanding their perspective proved indispensible to me. Both professions share the same ethics, or, at least, they should.”

Blair graduated with a bachelor’s degree in journalism the spring of 1973 and then earned a master’s degree from Washington University in St. Louis. Over the next 20 years, he worked in public relations for a variety of clients before starting his own agency in 1993. His success and life experiences, particularly in Los Angeles, led him to eventually share that success with his alma mater.

Practicing What Was Preached

Advertising was an integral part of American culture in the 1970s. The previous decade had brought about what was called the “creative revolution.” Agencies reacted by placing a growing emphasis on research and fact-based marketing. Advertising Age reported that 20 to 25 percent of all advertising accounts in the country moved from at least one agency to another over the course of the 1970s. A number of large agencies merged with smaller shops to maintain high business volume and by the end of the decade, there were no major independent U.S. agencies left on the West Coast.

This was the environment that Blair entered into after finishing his college education. Over the course of the next two decades, he learned that the only way to survive in the industry was to be flexible and willing to make necessary changes. Blair worked in Kansas City, St. Louis, Nashville, and then returned to St. Louis. His clients were in industries ranging from consumer goods and fashion to finance and healthcare.

“For me to keep my job in my area of interest, I had to do a lot of things I never anticipated doing,” Blair says.

In 1993, Blair was working as the public relations director for Barnes Hospital, which is affiliated with the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The University of Southern California offered him an opportunity to move to Los Angeles and soon thereafter, Blair was named the executive director of health sciences public relations and marketing. He represented the nation’s largest medical center and affiliated hospitals, including Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center.

Blair arrived in Los Angeles, when the LAC-USC Healthcare Network was battling what had become known as the HIV and AIDS. It had started in the 1980s, when the Center for Disease Control (CDC) published a report that described the lung infection of five, previously-healthy young men in L.A. They all showed indications of their immune systems not working, and two died before the report was published. They all had one thing in common – they were gay. The report marked the first official reporting of what became known in history as the AIDS epidemic. By the end of 1981, the CDC had received 270 reports of severe immune deficiency among gay men, 121 of whom had died.

AIDS became the No. 1 cause of death for men ages 25 to 44 in 1992. It was a year before Blair moved to Los Angeles and southern California was still at the center of the crisis. Hospitals and all areas of the healthcare industry were racing to find treatments and ways to care for those affected.

“It was an HIV holocaust,” Blair says. “It was no longer just gay men who were HIV positive. The disease didn’t discriminate. Given the opportunity, it could infect anyone. That’s what really caused the ball to start rolling and bringing national attention to the widespread epidemic.”

Blair faced a tough task as the voice of a hospital that was still being bombarded by a health epidemic that had spread worldwide. His training at the School of Journalism and prior experience in the industry had prepared him for the task to communicate to the public and within the hospital. He felt confident in his writing and skills as a public relations professional in healthcare.

In 1994, Blair left USC to open his own agency, BlairPR. He had built a reputation for healthcare public relations that he was able to carry with him in his new business. New technologies and advancements in the industry provided an opportunity for Blair to take control of his own destiny. BlairPR’s first client was Pacific Bell, a company that was looking to carve a niche for themselves in healthcare. Blair was hired to raise awareness and visibility for their new technology, one that would enable doctors to exchange imaging among themselves and with the USC hospitals.

“The idea of starting my own business was certainly on the horizon for me,” Blair says. “I had great expectations of myself, and I put a lot of work into what I was doing. I was probably my most demanding employer.”

“The idea of starting my own business was certainly on the horizon for me,” Blair says. “I had great expectations of myself, and I put a lot of work into what I was doing. I was probably my most demanding employer.”

BlairPR changed its expertise over the next several years as the landscape around it began to evolve. Funding started to shrink, closing the opportunities that were once available in the healthcare industry. Blair’s work moved into technology and then several consumer products. Crisis management became a large part of Blair’s agency work as well. He understood that he could be successful if he was willing to redirect his efforts depending on where the opportunity was. This was a lesson he learned well while working in the Midwest.

A Public Service Legacy Continues

Outside of work Blair has been an active member of the Episcopal Church, a denomination at the forefront of many progressive movements. In Los Angeles, an important mission of the church was to care for people diagnosed with HIV and AIDS. It was also front and center of the gay rights movement when it conducted the first same-sex union in the country in 1992.

Blair is a parishioner at All Saints Beverly Hills, where he is involved in pastoral care and serves as a lay minister. He completed a hospital chaplaincy program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where he was assigned to the oncology and cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit.

“It brought together my understanding of healthcare, my faith and my communication skills,” Blair says. “It was the greatest experience I’ve had in my life.”

Blair is now making his own mark on the family legacy in journalism by funding a project at his alma mater that will continue to change lives for years to come. In April 2015, Blair donated $1 million to the Missouri School of Journalism to create the Timothy D. Blair Fund for LBGT Coverage in Journalism. He is proud to say that it is the first donation of its kind in the country. The fund will provide support in understanding media’s role in the public’s perception of gender stereotypes. It will seek to understand the HIV and AIDS crisis as a force of rapid change and the advancement of LGBT civil rights within the context of same sex marriage and the overall fabric of American life.

“I’m 64 years old. I don’t know many gay men my age who are alive today,” Blair said at the gift announcement. “It’s a demographic gone missing from the gay community. It’s a story to talk about. I don’t think we have perspective yet, but I don’t think there’s anyplace that can do it better than the Missouri School of Journalism.”

Halli Bruton grew up in Springfield, Missouri. She graduated with a degree in science and agricultural journalism with an emphasis in strategic communication in December 2015. She is working at the Hurricane Junior Golf Tour headquarters in Jacksonville, Florida, as a marketing intern to fulfill her bachelor’s degree in parks, recreation and tourism. Bruton worked for ABC17-KMIZ News for three years as a production assistant. She interned for Crossroads, the public relations partner company of Barkley in Kansas City, during the summer of 2015.

Updated: December 11, 2015