Wayne Freedman

KGO News Team Reporter at ABC

Degree(s): MA '78

Whereabouts: United States, California, San Francisco

On a hot day in August 1977, Wayne Freedman flew halfway across the country to fight for his spot in the Missouri School of Journalism’s graduate program. Freedman, whose book is now a staple in broadcast journalism programs throughout the country, had already been denied twice because his undergraduate grades were not up to the University of Missouri’s standards.

He didn’t give up. Freedman wanted to become a broadcast journalist. He was convinced that the prestigious Missouri School of Journalism would help him succeed. He was so determined, in fact, that when he walked in the office of Dr. William H. Taft, who oversaw graduate admissions, he handed Taft a check for his entire graduate school tuition.

“I told him I earned that money. If I flunked out, he could keep the balance,” Freedman said. “I don’t know whether Taft was aghast, flabbergasted, or flattered, but he let me in on academic probation.”

Thirty-two years and 51 Emmy Awards later, it’s obvious that Taft made the right decision.

A Television News Man in the Making

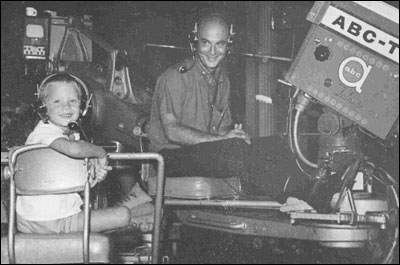

Freedman grew up in a town where the entertainment industry rules: Los Angeles. His father, Mike, was a director and producer at ABC Sports and pioneered the use of the first live, hand-held video camera at ABC News and ABC Sports. Mike Freedman’s passion for journalism rubbed off on his son.

“If you want to work in television, go do the news,” he told his son. “They never cancel the news.”

Freedman began writing formally at 14 years old while a ninth grader at Hughes Junior High School in Woodland Hills, a suburb of Los Angeles. One of the beats for the school paper required a weekly column for the Valley News and Greensheet, which later became the Los Angeles Daily News.

“I took that one,” said Freedman, “and continued writing for them through high school.”

Early on, he focused on finding the human element in stories.

“I used to spend time outside the Dean of Discipline’s office, writing our version of the crime report,” he says. “I learned that if you make someone or something interesting, you can write just about anything. The news isn’t necessarily line-by-line. Often, you can find the best stories between the lines.”

Freedman earned his undergraduate degree from the University of California at Los Angeles.

“It was the best school that would take me,” he says.

He wanted to major in journalism, but UCLA dropped that program after his first quarter.

“I began taking political science classes because at least they dealt with current affairs,” he says. “By junior year, I declared political science as a major because it was the shortest route out of there.”

One of the reasons Freedman’s grades slipped at UCLA is that he was working for ABC, first as a network page, and later in the local newsroom, cutting and pasting teleprompter copy for the evening broadcasts.

“They used to call me ‘Sneakers’ because I had to run 150 yards from the newsroom to the set,” he said. “I could do it in 20 seconds.”

Freedman also worked as a part-time production assistant for ABC Sports, where his father was a director and producer.

The country was in a recession when Freedman graduated. Jobs were hard to come by even for those with some experience. Freedman had been working 40 hours a week, writing columns for the Daily Bruin and even the L.A. Times. His dad, who had been covering college football games for more than a decade, knew of the Missouri journalism program. He asked then-master’s candidate David Smith, BJ ’73, MA ’77, to call and tell his son about the graduate program.

“Smith sold me in about five minutes,” Freedman says.

From the City of Angels to the Midwest

Freedman says that learning the pragmatic Missouri Method in Columbia was the best thing that could have happened to him.

“Learn that and you can make a basic story out of anything,” Freedman says.

In Columbia, Freedman discovered a more grounded set of values than he had grown up with out West.

“It was culture shock. I drove across the country thinking I was ready to work in the business,” Freedman says. “Then I saw younger kids doing more than I could in broadcast. The Missouri School of Journalism is a universe unto itself. That’s one of the reasons it is special. Total immersion.”

Freedman says that after gaining little traction as a reporter in a large market like Los Angeles, Columbia was a revelation.

“I worked for ‘the media,'” he says. “It was like a bolt of lightening: Awesome. Empowerment. Responsibility. Hope. Expectations.”

Before the end of his first semester, Freedman became a teaching assistant for a radio journalism class taught by professor Rod Gelatt. He had enterprised a radio story for NPR about Professor Taft’s 100-mile race walk. After that, the student on academic probation became the first TA from his class. Later he earned another assistantship at KOMU-TV, while earning mostly A and B grades.

“A’s for reporting. B for classwork,” Freedman says. “I’ll never be a model student.”

One of Freedman’s favorite courses in the first year was an introduction to newswriting. Classes took place in a room called, “The Pit,” because it was physically the lowest level class in the building. More experienced students walked above and looked down at the newcomers toiling away. The instructor would set up a fictitious situation. Students would grill him as if at a press conference before jamming out a mock story. To this day, when Freedman’s fingers hit keys, words flow.

“It taught students to meet deadlines,” he says.

Freedman attributes a large part of his success to the hands-on education he received from talented Missouri professors with real-world experience.

“As the saying goes, ‘those who can’t, teach’ – at the Missouri School of Journalism, those who can, or those who did, teach,” Freedman says.

Those professors reinforced his instincts. Freedman developed a philosophy that if journalists show the larger stories in small ones, and smaller stories in larger ones, then those stories will succeed.

“At least they think I did it their way,” Freedman says joking. “They taught that the facts mattered. They were real sticklers on the facts and making the deadline.”

Freedman’s class schedule, though demanding, still left time for a little mischief. As the end of their first semester in 1977, Freedman and some of his friends had some fun with the Missouri Honor Medal portraits hanging in Walter Williams auditorium, where Dr. Taft conducted his “History of Journalism” lectures.

“They were so stern-faced in those pictures – so serious, those elders,” Freedman says. “Taft was chiding our class about not having a sense of humor, so we saw that as a green light.”

Classmate Stephan Savoia took a low angle shot of himself with three Leica rangefinders hanging around his neck. Freedman sat at a desk with a typewriter surrounded by a mountain of wadded paper. His roommate, Jim Bates, posed with a pipe, looking stuffy.

“Our biggest challenge was finding matching frames,” Freedman says. “We finally found them at K-Mart.”

They hung their portraits among those of the other medalists. No member of the faculty said a word. Those pictures remained there until just before Journalism Week, when they mysteriously disappeared, never to be seen again.

Freedman still stays in contact with his closest Missouri journalism classmates. Bates, MA ’78, became a columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and Savoia, MA ’79, a multiple Pulitzer Prize winner. Others include Joe Bergatino, MA ’80, a former investigative reporter for WBZ-TV in Boston, and his girlfriend-turned-wife, Candy Altman, MA ’78, who runs broadcast news at Hearst, as well as Robert Gilmartin, MA ’79, a producer at NBC News.

Freedman felt he left the program knowing how to do everything he would need to do as a television journalist.

“From writing for newspapers, magazines and the news, to getting good sound bytes in interviews – those have all been important skills in my career,” Freedman says.

The Career of his Dreams

After graduation, Freedman worked in successively larger news markets, beginning in Louisville, and then moving to Dallas. When a former KABC colleague contacted him about a job in San Francisco, he jumped at the offer. He was 27 and had been out of school barely two years.

And so began Freedman’s 30-year career in San Francisco television news, where after eight years at KRON and two more with CBS News, he settled in at KGO-TV, the ABC-owned station. After 51 Emmy Awards, Freedman is still as passionate about telling stories as ever and wants to share his skills and wisdom with today’s aspiring journalists. His book, “It Takes More Than Good Looks to Succeed in TV News Reporting,” is a guide for journalists on how to create news stories in a narrative style. The book has been required reading at 50 universities, including the Missouri School of Journalism.

He began shooting and editing his own news stories in 2010, using skills he learned as a student.

“It’s amazing how what goes around comes around,” he says. “I still use the basic sequencing for shooting video skills they taught me more than three decades ago.”

Freedman has returned twice to the place that helped start his career. He gave a lecture about television news storytelling techniques at the Reynolds Journalism Institute in March of 2011.

After Freedman’s book was first released in 2003, he received a letter from Taft, who joked that he could not believe the kid he let into his school with so much trepidation had written a book to teach journalism students how to write stories. Of all the letters Freedman has received about the book, this is the one that he treasures the most.

“Thirty years later,” Freedman says, “I’m guess I’m finally off academic probation.”

Sarah Frueh is a strategic communication senior student and plans to pursue public relations. She oversees the promotional efforts of numerous campus events at the MU Department of Student Activities. Frueh also has interned at the Missouri Press Association and Bucket Media Co. in Columbia. She has participated in the Prague and Paris study abroad programs sponsored by the school.

Updated: November 28, 2011