Panel at Missouri School of Journalism unites 3 courageous journalists in discussion of press freedom

By Austin Fitzgerald

Photos by Nate Brown

COLUMBIA, Mo. (Oct. 3, 2025) — For the three veteran journalists who came together for a panel discussion on Tuesday at the Missouri School of Journalism, the story of David and Goliath is more biography than legend.

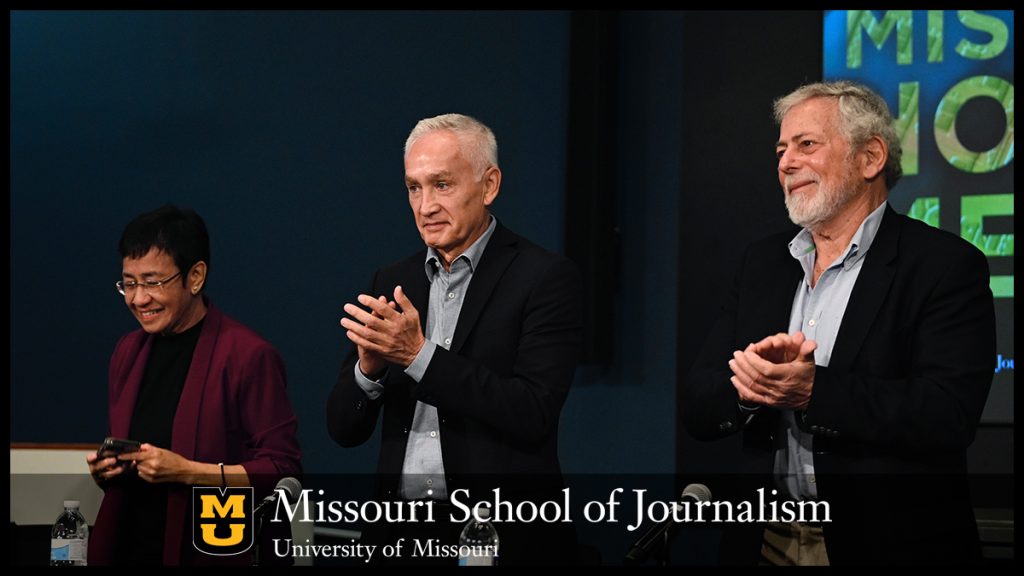

Gustavo Gorriti, Jorge Ramos and Maria Ressa have each squared off against dictators, censorship and intimidation, episodes that they spoke about in more detail during master classes later in the day. Against the backdrop of that common experience, the panel discussed the global trend of eroding press freedoms alongside moderator Kathy Kiely, the Lee Hills Chair in Free-Press Studies at the School of Journalism.

Ressa — who earned the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021 after enduring criminal charges, threats and intimidation from the Rodrigo Duterte administration in the Philippines — credited the organizing power of social media’s early days with helping her establish Rappler, a Filipino investigative news website that has exposed countless cases of corruption.

While Duterte is now detained by the International Criminal Court at The Hague, Ressa said dictators are not the only threats faced by proponents of free speech at a time when social media operated by for-profit tech companies exerts increasing influence on the public.

“Everything physical is being translated into the virtual world, and when we leave it in the hands of private companies to be that mediating interface…you have no idea how we are being insidiously manipulated,” Ressa said. “I want to get back to a shared reality so I can see what reality really is. I think that’s what we all have in common.”

A potential path back to that shared reality, she added, is a renewed focus on community in its online and in-person forms.

Ramos, the face of Univision for nearly 40 years, agreed and added that a healthy, functional community is one that is based around trust.

“I still believe that journalism is in us, in a universe where we’re flooded with lies and deepfakes and everything,” he said, noting that deepfaked versions of his likeness continue to circulate online in sales campaigns for dubious diabetes medications. “I live in Florida, and I trust two meteorologists who tell me during the hurricane season if I have to move or not…With journalists, I think we choose who we want to follow.”

Ramos said that choice is influenced by whether the public thinks journalists are doing enough to confront those in power, referencing his own confrontational interviews with authoritarian figures such as Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro. But rather than pressure the students in the room, he sounded notes of encouragement and hope, reflecting that if anyone can overcome the risks of technology to make it work in favor of journalism and community, it will be Gen Z.

“You’re the first generation that handles technology much better than we do, and you can choose whatever you want to do,” he said. “Tell the story that only you can tell.”

The undercurrent running beneath these topics of discussion was the importance of preserving democracy, something Gorriti made explicit when explaining the responsibility of journalists to dig deeply to uncover facts that those in power might not want exposed. (Gorriti wrote about his experience on the panel here.)

“We all know that without democracy, journalism — independent journalism — is not possible at all,” said Gorriti, who was kidnapped by agents of the Alberto Fujimori administration during Peru’s 1992 constitutional crisis as retaliation for his reporting on corruption.

As with Duterte, Gorriti’s own Goliath ultimately faced criminal prosecution, but like the rest of the panelists, Gorriti’s desire to make journalism an even stronger tool of public knowledge has only grown. And now, as news organizations have increasingly embraced the idea of working together to solve issues relating to everything from revenue models to legal challenges and free speech, he sees an opportunity for the industry to harness its own type of community to maximize the power of investigative journalism.

“We journalists are competitive by nature, but we have understood that collaboration and competitiveness are not mutually exclusive,” Gorriti said. “We can do the kind of journalism that was impossible before, and because of that, we can produce results which are far more hard-hitting than they were before.”

As an example, Gorriti contrasted the relatively solitary efforts of journalist Seymour Hersh to expose the Vietnam War’s My Lai massacre with more recent examples of collaborative, international investigations, such as the work of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (a 2023 Missouri Honor Medalist).

Perhaps the most vivid takeaway from the panel, then, was the image of a modern-day spin on the tale of David and Goliath — one in which Goliath faces not a single, solitary individual but is encircled by an entire team of Davids from all over the world.

Updated: October 3, 2025