Shuttered opinion pages. Obscene letters to the editor. Researchers at Missouri School of Journalism ask: What does it all mean?

Nick Mathews

COLUMBIA, Mo. (Sept. 26, 2025) — The relationship between news and opinion has never been a more hot-button issue. From national news powerhouses to smaller community newspapers, news organizations are re-evaluating how — and if — they publish opinion content.

Tracking this trend is a team of researchers led by Assistant Professor Nick Mathews at the Missouri School of Journalism. In particular, the researchers are interested in learning how practices differ between large metropolitan newspapers and small rural outlets when it comes to handling opinions.

“There just hasn’t been all that much research in this space, and especially recently as economic changes are happening, people’s expectations are changing,” said Mathews, who is also part of an informal research group at the School’s Reynolds Journalism Institute focused on supporting the community news industry. “We want to know, what are some best practices? What does it mean for a community when a news outlet pulls back on its opinion content?”

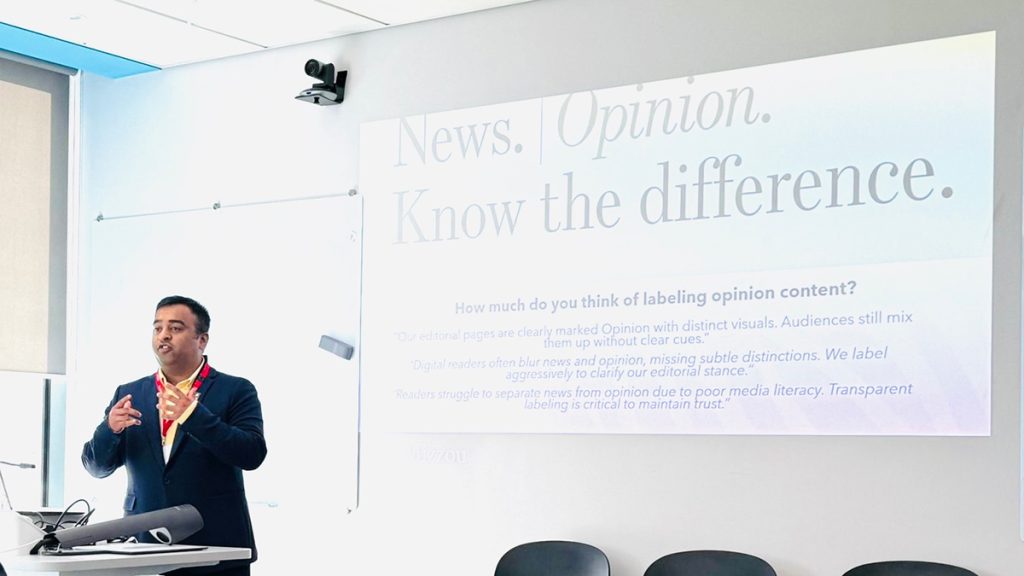

To answer those questions and many more, doctoral student Pranaav Jadhav is interviewing editors and managers of opinion pages at newspapers of all sizes, seeking to understand the philosophies and other factors driving their approaches to opinion pieces. Interviewing is nothing new to Jadhav; he has gathered professional experience throughout more than a decade in India and in the U.S., producing government and watchdog journalism, community reporting and even serving as lead producer on a documentary film. Earlier this month, he presented the research-in-progress at the Future of Journalism Conference in Cardiff, Wales, where a number of other School of Journalism researchers also presented their work.

The interviews are ongoing, but themes are already emerging, among them the importance of fostering news literacy in audiences to help them distinguish between news and opinion — a vital issue, Jadhav said, given that the line between the two is increasingly blurred by the prevalence of “hot takes” on social media and in some forms of professional journalism, such as sports reporting.

Perhaps a more surprising pattern revealed by the interviews is the pervasiveness of opinion sections run by a single person, especially at weekly newspapers and rural outlets. The one-man shop often extends to the writing as well, with “editorial board” bylines sometimes serving as a pseudonym for the opinion editor. Nor is it unheard of at small publications, Jadhav added, for the same individual to also run the news operation.

One area where large and small organizations are facing similar challenges, however, is that hallowed fixture of the American newspaper: the letter to the editor, another little-studied realm of journalism.

“Most of the editors are saying the letters have gotten unpublishable; the language is severely deteriorated,” Jadhav said. “The quality and quantity has gone down, so some editors will work with those unpublishable letters and say, ‘look, if you want to get published, you need to remove all this abusive language.’”

It’s a marked contrast from what one interviewee described as a hallmark of the beauty of journalism: the act of opening a paper with excitement and curiosity to see if one’s own letter has been published. As a variety of factors have lowered public trust in journalism and polarized social issues, letters to the editor seem to increasingly mirror the oppositional and highly emotional nature of public discourse.

Mathews said this shift points back to the larger issue of news literacy and helps explain why some newspapers — reluctant to drive a wedge further between them and the public — are reducing or entirely eliminating editorials and op-eds.

“Is The Wall Street Journal automatically conservative because of Rupert Murdoch? I would say no,” Mathews said. “This distinction is so important: The Wall Street Journal has some of the best journalists in the country covering significant events. Their news content has zero to do with the editorial product. But people will still say the Journal is leaning in that direction, or the New York Times is leaning the other way. So that’s one reason why people are making the decision to pull the plug on opinions.”

Yet even the publications pulling back on opinions continue to publish letters to the editor, reflecting a continued emphasis on elevating community voices to promote engagement with the news and civic issues alike. Mathews hopes this research will further inform those efforts

“It’s really exciting to dive into this data and see what we can learn and take back to news organizations,” Mathews said. “Maybe we have some advice from editors about how the heck to handle letters to the editor right now. We don’t know what all the insights are yet, but this project is coming across at a really important time. This is when this work needs to be done.”

In addition to Mathews and Jadhav, others contributing to the research are: Ryan Thomas, a former associate professor at the School of Journalism now serving as director of graduate studies at Washington State University; and Benjamin Toff, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota and director of the Minnesota Journalism Center.

Updated: September 26, 2025