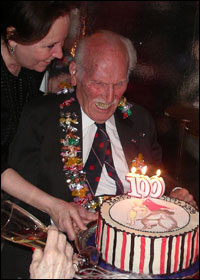

Missouri Journalism Alumnus Turns 100: A Look Back at the Life of an International Correspondent

Lester Ziffren, BJ ’27, passed away Nov. 12, 2007, at the age of 101 in New York City. The following story was written on the occasion of his 100th birthday in April 2006.

By David Wurtzel

Columbia, Mo. (April 24, 2006) — In the spring of 1927, a young man graduated from the Missouri School of Journalism with a mission shared by timeless reporters – to report the truth to citizens of a world filled with turmoil, trouble and triumph. Few journalists have fulfilled that mission as completely as Lester Ziffren, BJ ’27. From covering South American revolutions to breaking the news of the Spanish Civil War, Ziffren has filed reports on some of the 20th century’s most cataclysmic events. Sprinkle in encounters with Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Ernest Hemingway, Leon Trotsky and Thomas Mann, and Ziffren’s life story becomes an immersion into a rich history in which very few people can claim to have taken part.

On April 30, Lester Ziffren will add another accomplishment to his illustrious life – he will turn 100 years old. To honor his achievements, David Wurtzel, a London lawyer and relative, takes a look back at Ziffren’s life, as documented by his many diaries. The following recounts the pinnacle of Ziffren’s career as a war correspondent in Spain, along with his many other adventures. This short biography highlights a century of dedication by a true international journalist.

Turmoil in Spain

On the evening of July 17, 1936, the young United Press correspondent in Madrid, Lester Ziffren, BJ ’27, was in his favorite bar just before his nightly radio broadcast to the United States, “Spain Day by Day.” He was approached by the Marquis of Bollarque, one of the aristocratic friends he had made in the past few years. “Have you heard the news?” Bollarque asked.

“What news?” Ziffren said.

“It’s started,” Bollarque replied.

“Are you sure?” Ziffren asked.

“I am,” Bollarque said.

Since the afternoon, there had been rumors that something was happening in Spanish Morocco, but the Spanish government had denied it. Just before Ziff (as he was known to his friends) began his broadcast, his office rang to say that all telegraphic and telephonic communications with the rest of Spain and the outside world had been cut. As soon as he finished his broadcast, Ziff went looking for Fred Caldwell, the managing director of the Spanish National Telephone Company. Caldwell was having dinner at the Ritz Hotel; Ziff tracked him down in the men’s room. Caldwell confirmed that his company could not get through to Morocco either. With that, Ziff decided to go with the story.

He went to his office to discuss what to do with his team, men whom he had told, “We do not take sides; all I want from you guys is an honest report.” One man had a contact with government communications, and he agreed to ask the woman if she would give them a line to London. They went to the telephone company and begged the woman for 60 seconds to London. “This is absolutely illegal,” she said, but she allowed Ziff to call. London also knew nothing. He had a code, but London had thrown away their part. He knew that if he carried on and got the story out, he would violate government censorship – but this was important news that the outside world needed to know. Relying on his instinct for responsible journalism, Ziff broke the news. What he had to say was that there was a revolution in Spanish Morocco, led by Gen. Francisco Franco. What it in fact meant was that the Spanish Civil War had begun.

For the next five months, Ziff was UP’s war correspondent in Madrid. He avoided sniper bullets, gave up wearing a hat and a tie (“That’s bourgeois, and this is a hell of a time to be a bourgeois,” he wrote at the time.), and confessed to his parents in Illinois, “Couldn’t walk out on this story for anything, otherwise, why be a newspaperman?”

The Life of a Newspaperman

Ziffren acquired the taste for journalism as a youth in Rock Island, Ill., when he persuaded the town’s paper to let him cover the local golf tournament. He eventually landed at the Missouri School of Journalism, where he was editor of the Omegaphone and won the John W. Jules Scholarship for Journalism.

“What I got out of journalism school,” he later recalled, “was a respect for the truth. We had a responsibility to the public. A set of principles. Objectivity. Writing that you can learn on your own, from experience.”

When the president of United Press attended the School’s graduation dinner, Ziff took the opportunity to ask him for a job and got one. A year later he was sent to Buenos Aires. In the next four years he covered half a dozen South American revolutions. When he spoke a dozen years later in California, he was introduced as “here’s someone who’s been in hot water all his life.”

In New York in 1933, Ziff worked at the United Press cable desk and was sent to Washington to cover a press conference with FDR. On Manhattan evenings he would walk through Rockefeller Center as it was being finished, and struck up an acquaintanceship with famed artist Diego Rivera, who was working on the famous murals which were later destroyed.

Ziff arrived in Madrid in June 1933, just as dissatisfaction with the Second Spanish Republic was starting to escalate. Almost immediately he developed a lifelong passion for bullfighting. He also demonstrated his extraordinary ability not merely to interview but to be liked and accepted by the great men he met. Claude Bowers, the U.S. Ambassador to Spain from 1933-1939, would invite him round every Sunday to hear his views. The visiting Ernest Hemingway brought Ziff into the Hemingway circle of bullfighters and artists. “Damn glad to hear from you,” was how his letters to Ziff over the years always began.

Ziff did have to leave Spain, in December 1936, after Franco, who had become leader of the uprising, threatened to “deal” with Ziff because of what he had written about the Caudillo’s intelligence sources; Franco had proclaimed himself Caudillo, or “chieftain,” a few months into the rebellion. Ziff eventually made his way to Los Angeles, to see Edythe Wurtzel, the daughter of a Hollywood agent whom he had met in Madrid in May 1936. Although offered the UP job in Rome, he decided to stay in L.A. to marry Edythe and to become a scriptwriter at Twentieth Century Fox, where Edythe’s family worked. The couple spent their honeymoon in Mexico. He took off an afternoon to talk to the exiled Leon Trotsky, one of the leaders of the 1917 Russian Revolution, who wanted to hear about the Spanish war but forbade Ziff to publish the interview.

Edythe and Ziff bought a house in Pacific Palisades. Down the street lived twins Julius and Philip Epstein, who would give Ziff a ride to the studio. He was at Fox, working on Charlie Chan movies; they were at Warner Brothers, working on the script of “Casablanca.” Across the street lived Thomas Mann, with whom he would talk when the great writer was taking a walk with his dog. Sometimes, the Ziffrens would “babysit” Mann’s dog.

A Career Change in South America

When the United States entered World War II, the U.S. Ambassadors in South America were told they must have a public relations officer. Claude Bowers, now ambassador to Chile, insisted on having Lester Ziffren. So the Ziffrens spent the war in Santiago, as part of Nelson Rockefeller’s Inter-American Affairs Department. (Sixty years later, the biographical film “Frida,” about artist Frida Kahlo, depicted Kahlo, Rivera, Rockefeller and Trotsky; Ziff may be the only person who knew all four of them.) Ziff’s first task was to get the Chilean government to break off relations with the Axis powers. He did it by orchestrating an editorial campaign in the newspapers of the other countries, lamenting the fact that Chile was standing out in this respect. “I got the ball rolling,” he said, and Chile did in fact break off relations.

Returning to Los Angeles in 1945, Ziff took over his late father-in-law’s Hollywood agency. For his work in Chile, Ziff later received an honor from the local consul on behalf of the Chilean government’s foreign office. Thomas Mann and Rita Hayworth attended the ceremony. In 1952, Ziff returned to the State Department. After service in Bogota, Colombia, and Santiago, Chile, as the first secretary, he left the foreign service to become head of public relations for Braden Copper, the Chilean subsidiary of Kennecott Copper. Edythe was a noted hostess, and Lester was successful in gaining the understanding of instinctively anti-Gringo locals who had never in fact met a North American. He felt that his background as a journalist stood him in good stead there, since his job as a reporter was to observe and not to condemn.

In 1961, Lester, Edythe, and their daughter Didi went to live in New York. He became Director of Public Relations for Kennecott, the largest copper company in the world. After he retired, he was called back to produce a white paper (an authoritative report) on Chilean president Salvador Allende’s expropriation of Chilean mines; this white paper was used at the International Court hearing in The Hague in which the company was successful against the Chilean government. Edythe died in 1977. Lester helped to found the North American-Chilean Chamber of Commerce. As he reaches his 100th birthday on April 30, 2006, he remains true to his journalistic instincts: Each morning he reads three English and one Spanish language newspaper, and each afternoon he clips interesting articles from them to send to his friends around the world.

Updated: April 28, 2020