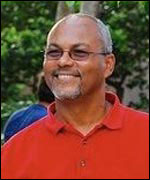

Yves Colon, MA ’90, Serves Haitian Radio Audience Recovering from Recent Earthquake

By Holly Edgell

Assistant Professor

Missouri School of Journalism

Columbia, Mo. (Feb. 17, 2010) — Journalists from around the world arrived in Haiti soon after the Jan. 12 earthquake and started filing stories of survival, devastation, sorrow and hope to people far from the rubble and despair. Anderson Cooper and Dr. Sanjay Gupta of CNN, as well as Lester Holt of NBC were among the many other high-profile news media professionals who shared information about the situation on the ground on the air, through blogs and Tweets.

All the while, a much smaller, very low-profile group of journalists was also busy, providing life-saving information about resources and daily conditions to a Haitian audience. Truly, this was news the locals could use.

Yves Colon, MA ’90, and a former faculty member at the Missouri School of Journalism, is part of a small Internews team providing news and information by radio for people around the earthquake zone. Time recently did a short video on their work for its online edition.

This is not Colon’s first time covering a big story in Haiti. In 1986 he was a stringer for The Associated Press after Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier left for exile. From 2003 to 2006 Colon led a project helping community radio stations there.

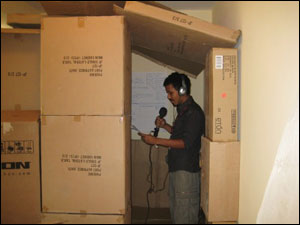

Now living and working out of a bare bones facility in Port-au-Prince, Colon spared a few moments to describe his experiences and work to me.

HE: How soon was your radio operation via Internews up and running after the quake? What were some of the logistical issues you had to deal with to get things going?

YC: My colleague, who’s a fantastic radio journalist who has done emergency journalism in Ache after the tsunami, and I got here on Jan. 20, a week after the quake, and we got the program going the next night. So, a week after the quake, but one night after we drove across the border from Santo Domingo.

HE: Your crew delivers radio programs to the stations on CDs. How many times a day? How many stations?

YC: We deliver CDs once a day to 28 radio stations, 25 commercial radio stations in Port-au-Prince and three community radio stations. Moto taxis deliver those CDs for us. The stations broadcast our program several times a day.

HE: You live and work in your “studio.” I imagine the adrenaline and sense of purpose is fueling your efforts and keeps you positive, but what kinds of morale issues are you and your team dealing with? There must be frustrating moments.

YC: Indeed, there are frustrating moments. I’ve been working and teaching journalism in the U.S., where journalists have all the tools at their disposal: freedom of press laws, legal support, computers, the net, etc. Plus, the big part is that American journalists grow up in a culture where they’re expected to question everything. That’s not the case here, where journalists don’t ask questions, are timid before authority, and take everything as is. They don’t question authority, and it can be frustrating to get through that, but they’re trying. The mentality has to change for journalism here to play the role of watchdog, which is going to be needed big time since billions of donor dollars are going to be steered here.

HE: Are any of your reporters dealing with losses of family and friends due to the quake? How are they coping?

YC: Everyone here is dealing with loss. One of our reporters had to rush out today to attend to a 23-year old friend who has threatened suicide. Another reporter, who’s a single mother of a 9-year-old and an 11-year-old, is homeless. She has to transfer four times on tap taps (pickups turned into buses) to make it here. Another one pulled his wife out of a collapsed building. More than a dozen journalists lost their lives in the earthquake, according to Reporters Sans Frontieres. Those who survived lost their jobs because radio stations no longer have ads. The newspapers here stopped publishing, and those journalists are out of work, too.

HE: How does this experience of covering a post-disaster situation in your native land compare to crisis coverage you may have done elsewhere?

YC: Totally different. I’m a lot more emotional here. I’ve covered an earthquake in San Salvador, and I was removed from it. I was interviewed by a radio journalist for the Miami NPR affiliate, and I broke down in tears. A couple of days before I had walked downtown and saw firsthand how the whole city was devastated. I had only seen things like that in movies, rubble on both sides of the street, people walking around stunned a week after the quake. It reminded me of a war zone, of pictures I had seen of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, desolation, no life, and I wondered if life would ever come back to that place. People were walking around with bandaged arms and legs, laying out on the street. And doing what I do, I know that one million people are living in temporary camps because they’ve lost their homes. Haitians, as the U.S. and European press says, are the poorest people in the Americas. I couldn’t help thinking that they had little to begin with and now they had even less than that.

HE: Recently the Society of Professional Journalists admonished journalists on the ground in Haiti to “cover the story, don’t become part of it.” What are your own thoughts about what is crossing the line into becoming part of the story and helping or advocating for the people you are covering? Have you found yourself straddling this line or even crossing it? If so, please describe.

YC: No, I don’t have that problem because I know exactly what I’m here for. I’m here to help get information to people who need the information to survive. As a Haitian American I feel part of the story, but as journalist, I am not part of the story. I try to get our reporters, who are all Haitian, to be fair, but to keep thinking about their audience, which is made of internally displaced people, or IDPs. We write about the help that’s coming from all over the world without bias.

Updated: May 7, 2020