Celebrated Photojournalist Delivers Two-day Seminar on Fundamentals of Web Video

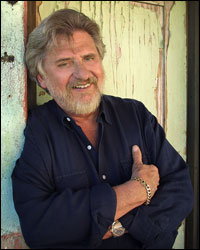

Columbia, Mo. (Oct. 26, 2007) — In November 1982, Time-Life photojournalist Dirck Halstead had an epiphany while shooting his first-ever video at the unveiling of the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington D.C.

“I became aware that as a photojournalist I had been leaving behind 50 percent of the story,” Halstead said. “This was the turning point of my life.”

Twenty-five years later, Halstead now travels to newspapers and universities around the country helping introduce still photographers to the possibilities of video. He visited the Missouri School of Journalism Oct. 10-11 to deliver his “Platypus Short Course,” a two-day crash tutorial based on his standard nine-day workshop.

The workshop surfaced as a result of Halstead’s Platypus Papers, a manifesto he wrote in 1997 that compares new-age visual journalists to the platypus, a species that defied established classification systems. Through the Platypus courses and his work as editor and publisher of The Digital Journalist, a multimedia online magazine, Halstead has redefined the roles and skills of a photojournalist.

The two-day course “gave our students an incredible opportunity to learn from an acknowledged leader in the industry,” said David Rees, associate professor and chair of photojournalism. “Our photojournalism students benefit from learning to shoot video because it will enable them to get internships and jobs.”

Journalism is changing, Halstead said in the course introduction Oct. 10. The print behemoths of 10 or 20 years ago are embracing the Internet as a means to counter plummeting circulations and to garner more youth interest. Central to that Internet presence is Web video.

“Here’s where it comes to you guys,” Halstead told the 30 or 40 student journalists crowded inside Tucker Forum. “There are very few people who know how to do it. People who master this skill are in high demand.”

For the beginning videographer, Halstead offered a short list of guidelines: hold the camera steady or use a tripod, frame the shot as you would with a still camera, roll each shot for 10 seconds or more, and avoid pans and zooms.

Halstead walked the students through hypothetical news scenarios, at one point dimming the lights and asking students to close their eyes as he described shot-by-shot how to cover a structure fire. “The camera is there as an observer, a vessel, to tell the story, the whole story,” he said.

Anjali Pinto, a freshman photojournalism major, attended both days of Halstead’s seminar. She’s spent the past four years learning still photography, but said she knows she’ll need to be flexible in order to land a job after graduation.

“It’s almost a necessity, I feel like,” Pinto said about learning how to shoot video. “It has a powerful effect on viewers, and you’ve got to keep up with the competition. It’s important to get an early start.

“Halstead is really knowledgeable,” she added. “I’m a visual learner, and it helps for me to see examples. It really made a big difference.”

Graduate student Mu Li, who is in the first semester of the convergence program, said the two-day workshop helped clarify what she’s currently learning about video.

“I especially like his critiques of the videos,” she said halfway through the second day. “These are things we would normally look at but not think too much about. It’s a very intensive program.”

Halstead, who accepted a Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism Oct. 9, is a senior fellow in photojournalism at the Center for American History at the University of Texas. He spent 29 years covering the White House for Time Magazine, where he shot a record 51 cover photographs.

Updated: April 21, 2020