2016 U.S. presidential election coverage was ‘game changer’ for journalists

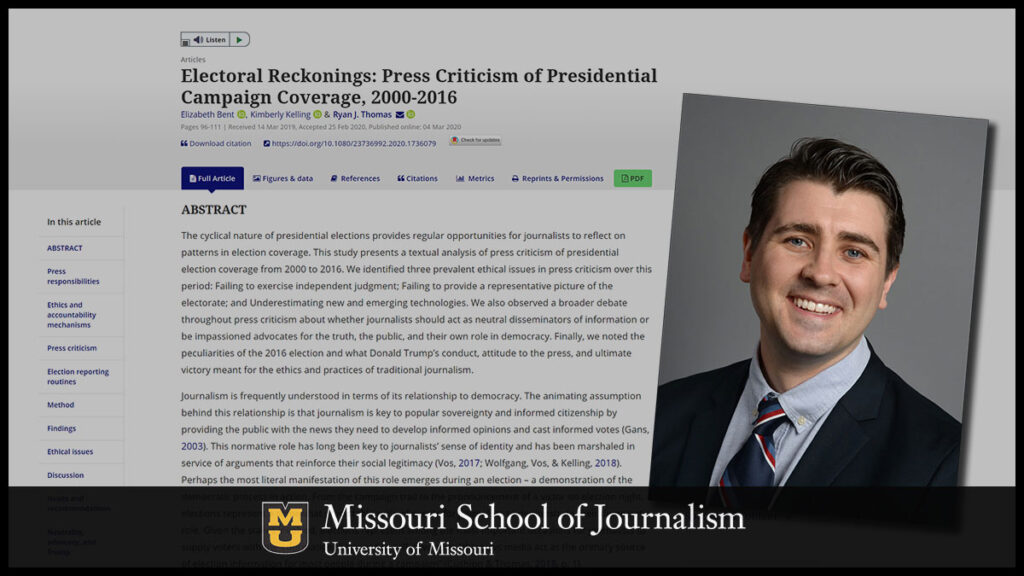

According to Ryan J. Thomas, associate professor of journalism studies at the University of Missouri, the 2016 presidential election is considered a “game changer” because it introduced the issue of how journalists confront political candidates.

MU study looked at ethical issues in U.S. presidential election press coverage between 2000-2016

By Eric Stann

MU News Bureau

Columbia, Mo. (June 22, 2020) — The 2016 U.S. presidential election is considered a “game changer” for journalists covering the U.S. presidential elections by causing them to dramatically reconsider how they view their role – either as neutral disseminators of information or impassioned advocates for the truth – according to researchers at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism.

“The 2016 presidential election is considered a game changer because it introduced the issue of how journalists confront political candidates – should they call out a lie and be more aggressive with checking the facts or do these actions violate the principles of journalistic neutrality,” said Ryan J. Thomas, an associate professor of journalism studies. “While there are different views among the critics, the fact that this issue appeared in 2016 suggests there is something particular going on that hadn’t been seen before.”

A relatable example of this issue today can be found in the form of the presidential press conferences during the COVID-19 pandemic, Thomas said.

“In theory, these daily presidential press conferences about the COVID-19 pandemic ought to be a space for sharing critical public health information but instead they take the form of a political rally,” he said. “News organizations have wrestled with the question of whether to run those press conferences live, with mixed results.”

Thomas said this issue also highlights a broader debate about journalists’ role in a democracy since the 2016 election.

“Journalism serves its democratic role through election coverage by providing the public with news they need to develop informed opinions that they can then use to cast their votes,” he said. “With the 2016 presidential election, there was a shift towards self-advocacy in journalism. Rather than journalists assuming if they do their jobs, everything will be fine and their audience will trust them, now there is a lot of talk suggesting journalists need to self-advocate for their roles during a time when their work is being criticized as ‘fake news’ and they are being called ‘enemies of the people.'”

Using a custom database funded by the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute, the researchers looked for patterns in ethical issues identified by press critics in over 300 press articles that covered the presidential elections between 2000-2016. They identified three common ethical issues over this period: failing to exercise independent judgment; failing to provide a representative picture of the electorate; and underestimating new and emerging technologies.

Thomas notes that while press critics have long reported about journalists facing criticism for their coverage of presidential elections, these common ethical issues highlight an important ongoing debate about election coverage within newsrooms: coverage of “the horse race,” or who is winning or losing, or doing investigative and analytical reporting of candidates’ policy issues. Thomas believes this is a structural problem within journalism.

“I don’t believe we can pin all of the blame for this problem on journalists who are increasingly having to do more with less,” Thomas said. “We suggest that the industry needs to look at economic incentives at the executive management or corporate level. Journalists themselves may not be on the right level to affect these changes.”

The study, “Electoral reckonings: Press criticism of presidential campaign coverage, 2000-2016,” was published in the Journal of Media Ethics. Co-authors on the study include Elizabeth Bent at MU and Kimberly Kelling at University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh. Funding for this study was provided by the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Updated: November 13, 2020