Monique Luisi: The making of a Missouri School of Journalism scholar and educator

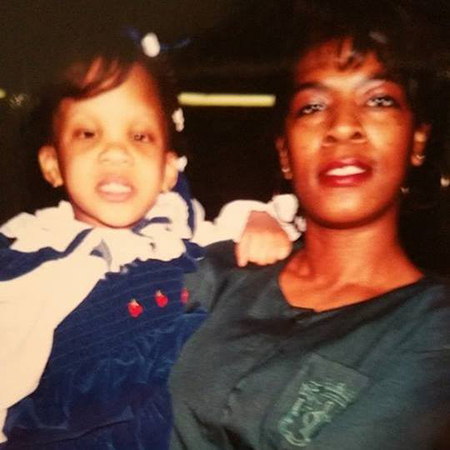

Columbia, Mo. (Jan. 13, 2022) — Monique Luisi awakened to the importance of science communication earlier than most. When she was just four years old, her mother suffered a series of strokes that required an extensive recovery. Young Monique not only motivated her mother to relearn speech and motor skills, but also listened to doctors speak in a jumble of medical jargon that neither she nor her mother could fully understand.

“As a kid, I thought it was cool that I was helping my mom by learning a bunch of medical terminology,” Luisi said, “but I realized later, ‘Oh, it’s kind of not cool that doctors were talking so fast, and using so many big words, that my mom couldn’t keep up with it all.’”

Ultimately, the experience taught Luisi that clear science communication can be a life-or-death issue, and that there was a dire need for improvement.

Now an assistant professor of strategic communication at the Missouri School of Journalism, she has turned those insights into a career focused on understanding how the public interacts with scientific information, both as a researcher and a teacher. Currently, much of her work revolves around how the public perceives vaccines, and the impacts of different forms of communication on those perceptions.

But while her career path seems like destiny — she filled out her first college application at the age of nine as part of an elementary school assignment — that path didn’t always seem so inevitable, even as life seemed insistent about leading her toward education and communication. Her story is about persistence.

“Teachers saved my life”

Luisi’s mother raised her as a single mother on a fixed income. Luisi recalls struggling with her identity as a Black girl in Montgomery County, Maryland, a majority-white, majority-wealthy county adjacent to Washington, D.C.

“Mom didn’t want me to think of myself as a little poor Black girl,” Luisi said. “There were some things that really hurt me growing up, and I didn’t understand why people would say hurtful things. But mom taught me that a person’s circumstances shouldn’t discount them.”

Growing up, she felt stranded between communities. She heard it all: backhanded, racist remarks about how she “talked so well;” scornful comments about “bad blood” passed on to her by her father, who went to prison early in her life; the notion that she “acted white;” the question, “no, where are you really from?”

There was an uneasy sense, too, that the path toward success was tenuous — that she needed to be constantly vigilant to avoid falling off her path. One image stands out in her memory: a kid once got his teeth knocked out at the bus stop, right in front of her. Blood splashed on her shoes.

Overwhelmed and angered by her experiences, she began to act out. But her future intervened again in the form of Black teachers who helped steer her back onto her path, including Mr. Hunt, a middle school social studies teacher.

“I got tired of not fitting in,” Luisi said. “So I started trying to act cool, started cursing, trying to act like what I thought people wanted me to be like. Mr. Hunt pulled me aside and said, ‘Monique, stop that. That’s not what you’re about.’ And that kind of woke me up. So while people have said hurtful things, I’ve had a lot more people believe in me. I feel like teachers saved my life.”

The early influence of education in Luisi’s life also helped her mother, Debra Robinson, tackle the unique challenge of raising a child by herself while also depending on that child to help her recover from her strokes.

“I used to sit with Monique while she did her homework,” Robinson said. “It felt like I was going to school. I rehabilitated myself through Monique.”

A special connection

Despite the impact of her educator role models and her own fierce desire to learn, the common thread in Luisi’s path toward a career as a scholar and educator has always been Robinson. Beyond the early crash course in the importance of health communication, the bond between mother and daughter nurtured a firsthand understanding of the benefits of clear and open communication.

“My mom protected me, but she never lied to me,” Luisi said. “She never sugarcoated topics like disease and death; we’ve always been able to have honest conversations.”

Robinson attributes some of that frank honesty to an early sense of what her daughter could do if given the opportunity.

“When Monique was an infant, I saw something in her,” Robinson said. “I said, ‘she’s a different child. She’s going to be something. And I’m going to make sure I do what I can do to help her get there.’”

Now, in her work studying why people do or don’t trust vaccines, Luisi is paying it forward by teaching the world about the role of communication in public perceptions of vaccine campaigns and other health messaging. In 2020, she published two studies exploring how negative perceptions driven by social media can cause people to avoid the vaccine for human papillomavirus (HPV), a common infection easily prevented by vaccination. One of those studies showed that this avoidance also occurs in parents who refuse to vaccinate their children for HPV at the recommended early age because social media has convinced them it could be lethal.

Naturally, her work on the HPV vaccine — including a project with fellow strategic communication professor Shelly Rodgers examining public service announcements — has also led to ongoing studies on the public perception of COVID-19 vaccines. One of these projects is investigating how a positive or negative experience with the COVID-19 vaccine might predict a person’s willingness to receive other vaccines, such as those for shingles or HPV.

But Luisi’s work does not focus solely on health communication. As a co-principal investigator on a grant from the U.S. Department of State, she is preparing to help train journalists in Niger to identify terrorist messaging and combat disinformation. The trainings will begin later this month, and Luisi will be tasked with evaluating how much participants have learned from the sessions.

Giving back as an educator

Though Luisi understands — perhaps better than most — why her research is important, it’s teaching that she finds most rewarding. She serves on the board for the Teaching for Learning Center, which supports instructors at Mizzou with programs and partnerships providing professional development.

“I won’t lay on my deathbed and think about research I wish I’d done, but I will remember teachers and students,” she said. “Teaching is what really gets me excited.”

She remembers the teachers, good and bad, who made the biggest impressions on her. There was the kind and observant Mr. Hunt, but there was also the elementary school teacher who shoved her against a wall and threatened her. Then there was Ms. Campbell, who helped her course-correct the next year when lingering anger about the incident caused her grades to slip.

“I think it’s important to give back, because those are the things you remember,” she said. “I want to have a positive impact on my students.”

And what of Robinson, Luisi’s first teacher and original role model? How would she describe her mother in one word?

“I’m phenomenal,” Robinson cut in.

No disagreement from Luisi.

Updated: January 14, 2022