Why Students Should Understand How to Cover Trauma

By Katherine Reed

Republished from PBS MediaShift by permission.

What are the must-teach fundamentals of journalism?

Put 10 instructors in a room and you’ll get ten different answers to that question. You would hear about accuracy. Data skills. Verification know-how. News-gathering and editing skills across platforms. Strong writing. Social media agility. An understanding of audiences and metrics. Cross-cultural sensitivity.

Another fundamental skill is worthy of that list: understanding how to cover traumatic events, including:

- what trauma is and how people respond (differently) to it;

- how to avoid inflicting more harm on people or communities in recovery;

- how journalists can be affected by the stories they cover.

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma has raised the consciousness of journalists, newsroom managers and J-Schools all over the world. But it’s slow going in the last category. In 2013, when she did a survey of trauma and crisis reporting education in the U.S., Amy Schmitz Weiss at San Diego State University found that only 12 percent of the journalism educators surveyed were teaching a course on trauma reporting though most of those surveyed thought it was important to teach these courses.

At the Missouri School of Journalism, I’m teaching a course called “Covering Traumatic Events,” thanks in part to training I received at Dart. This is what I’ve learned: teaching students about trauma addresses vexing problems in journalism and offers elegant solutions to them. It prepares students to be more sensitive to the people they report on, do better, more ethical reporting on trauma and recovery, and might actually improve journalism and how journalists are perceived by the public.

It also teaches future journalists to be aware of their own mental and emotional health as they cover the daily grind of violence in their communities, disasters, and perhaps even conflicts. Maybe, just maybe, it can prevent early burnout.

What they learn in the process is how resilient human beings are — including themselves — and the role that journalism can play in helping people and communities pull together and spring back from a blow.

What It Means To Bear Witness

Journalism students crave conversation about journalism’s central purpose and what it means to be a journalist. Sometimes, we teach across a divide because we make the mistake of thinking that we’re all operating according to the same set of assumptions.

When there were fewer sources of news and they all seemed to be doing basically the same thing, what journalism is and what a journalist does was clearer. Now, news is far more diffuse, arriving in a gazillion different forms from a gazillion sources (gazillion might not be an exaggeration).

A close look at trauma reporting helps dispel some of the fog because it clarifies the most basic and important purpose of news-gathering: bearing witness.

It’s deceptive in its simplicity. What does it mean to bear witness? Why do we have to do it? What can be done to minimize the potential harm that witness-bearing can inflict on people caught up in traumatic events, the elderly man who has just lost his home and most of his hometown to a killer tornado? Or the sexual assault victim who wants to tell her story and attach her name to it?

And what does all of this cost us as human beings? What does it cost us in physical and emotional well-being? What does it extract from our souls?

As Barry Malone wrote in Al Jazeera recently, “Bearing witness is grueling,” especially when there are so many important things journalists hope to make people care about. The effort can drain us, and students should be prepared for that.

Trauma As Fault Line

Teaching about trauma helps students get over their discomfort about talking to people across fault lines because bad luck has no boundaries. Trauma itself might just be a kind of fault line.

Misfortune sometimes creates an invisible barrier around the people who’ve suffered it. Sometimes students think the best choice is to not make the call to the grieving parents or the sole survivor of the fire. They don’t want to be “that guy” – the stereotypical, unfeeling journalist of TV and movies (and sometimes, sadly, real life), shoving the microphone into the face of tragedy and asking for a quote.

A 2008 University of Florida study of the effects of the media “mob” after the Virginia Tech shootings found that the individual behavior and sheer number of journalists worsened the trauma of survivors.

Can journalism afford to screw this up over and over? I don’t think so.

But we also can’t report on recovery and resilience if we stay away. Teaching Frank Ochberg’s Three Acts of Trauma helps students see how much attention the media pay to the breaking news of trauma — Act I — and, too often, how little is paid to what comes after, Acts II and III.

When I invited to class the mother of two children who were electrocuted in a recreational lake not far from the city where I teach, she told my class she couldn’t remember much about those first days after their deaths. Friends and family told her later about the TV reporter whose lights and camera were already on when he rang the front door of the family’s home. And about the reporter parked in her car at the end of the driveway, visibly sobbing inside (the reporter told the concerned neighbor who knocked on her window that her editor wanted her to talk to the parents and she didn’t want to do it).

What puzzled the mom most was why “no one came back to see how we were doing” in the long, hard months that followed. It bothered her that most people knew nothing about her children’s lives and a lot about their deaths — some of it incorrect and painful to read or see on television. She talked about how much it meant to her that the Columbia Missourian, where I teach, published an obituary/feature about her son and daughter, who they were, and what they loved.

That story helped, she said. So she saved it.

The reporter who did the story was afraid to make the calls, but she found out that sometimes people don’t just want to talk; they need to talk. Journalists can let them do that.

Building Ethics Muscle

Teaching about trauma means discussing ethics. A lot.

I’ve had several students decide after taking the class that they could never be the photojournalist who shoots a picture of someone trapped in the rubble after a disaster and then just walks away. We talk frequently about when journalists should intervene, when they should just stick to the reporting, and when those two important duties as human beings are compatible.

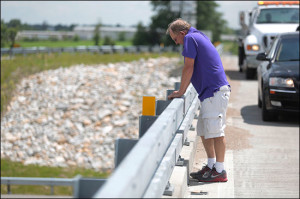

The subject matter also prompts some very deep thinking about the use of graphic images in storytelling and the impact they can have on survivors and a community. It’s not enough to develop this ethical decision-making muscle in photo and photo editing classes. Anyone with a smart phone can capture an image at the scene of a fatal car crash and Tweet it.

As journalism has evolved from a one-to-many to a many-to-many activity, journalists have to rely more than ever on themselves and their own humanity. Many are working with fewer editors and less oversight.

That means being equipped with a pretty reliable moral and ethical compass.

Getting lost has serious implications for the journalist — the human being — and for trauma survivors.

And for journalism.

Updated: September 8, 2020