Friends of the Facts conference at Missouri School of Journalism promotes media literacy through conversations with national experts

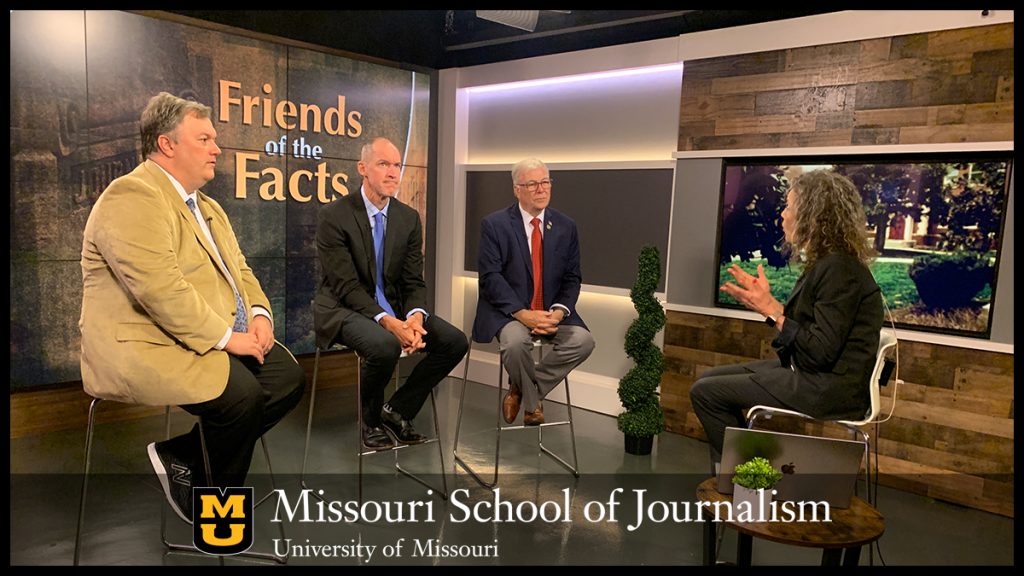

Professor Kathy Kiely, right, Lee Hills Chair in Free-Press Studies, speaks with her panelists June 27, 2022, during her virtual Friends of the Facts seminar. With her in the RJI studio are, left to right, Jason Artman, an Illinois high school teacher; Shawn Healy, Illinois iCivics; and Rep. Jim Murphy, a member of the Missouri House of Representatives. The panel: Should we require schools to teach digital literacy?

Photo by Nate Brown | copyright: 2022 – Curators of the University of Missouri.

Columbia, Mo. (July 12, 2022) — At the end of June, experts in media literacy and digital wellness from around the country spoke during Friends of the Facts, a week-long virtual conference at the Missouri School of Journalism. Aimed at promoting informed consumption of digital media amid the rise of “fake news,” deepfakes, and misinformation, the conference featured 11 interactive sessions from June 27-30, which are available for viewing on the Reynolds Journalism Institute’s YouTube page.

“In the information age, learning how to evaluate sources and distinguish fact from opinion can’t be skills reserved only for reporters,” said Kathy Kiely, the Lee Hills Chair in Free-Press Studies at the School of Journalism and host of the conference. “We’re living in the aftermath of a technological revolution that has profoundly altered the way we communicate, and every form of new technology can be used for good or bad. It’s on us, the users, to decide which it’s going to be.”

To that end, sessions featured subject matter ranging from how to spot deepfakes and disinformation to communicating across digital and cultural divides, as well as strategies for managing the dangers to physical health posed by misinformation and “information overload.” Together, these topics fell under the broad umbrella of news and media literacy, encouraging viewers to think not only about what media they consume, but how they consume it.

“Instead of just being a constant consumer of information, a news-literate person asks questions and understands why the messages are chosen, how they’re designed, how and why they’re presented the way they are,” said Julie Smith, an author, speaker and communications instructor at Webster University, in a session discussing how disinformation can disrupt social and emotional learning. “I think that helps people see behind the curtain and change the relationship we have with all the information we consume.”

How do we take advantage of all the choices the internet offers us without falling prey to charlatans or curating our way into our own tunnel vision? How do we learn to recognize the news equivalent of empty calories and work some whole grains back into our information diet?

Another speaker, Monique Luisi — assistant professor of strategic communication at the School of Journalism — discussed the importance of tailoring messages to specific audiences and drove home the risks of using social media to combat disinformation or misinformation that might have itself originated on social media.

“It is so efficient to put out information on social media to combat social media information,” Luisi said. “But that’s not necessarily the most effective tool. We have the means, we have the people, we have the skills to communicate with people at an interpersonal level. Yes, it takes more work, and it takes longer, but the outcome is so much more rich and effective than posting anything on social media to combat misinformation.”

Viewers were able to ask questions during live sessions, and those who were unable to watch live could submit questions in advance. The mix of live and pre-recorded virtual sessions — a fitting format for discussions surrounding the digital age in media and technology — usually took the form of conversations with Kiely, KOMU-TV anchor Taylor Freeman, and expert speakers.

For Kiely, this format was a reflection of the topic’s status as an ongoing conversation in society, one with few easy answers but with opportunities for progress through earnest discussion.

“How do we take advantage of all the choices the internet offers us without falling prey to charlatans or curating our way into our own tunnel vision?” Kiely asked. “How do we learn to recognize the news equivalent of empty calories and work some whole grains back into our information diet? That’s what we came together to discuss. With any luck, tackling these questions has turned out to be a super spreader event for a good kind of virus: one that will make us savvier users of the internet and better citizens of the digital world in which we all live.”

In addition to Smith and Luisi, featured experts included:

- Jonathan Anzalone and Howard Schneider: Founder and assistant director, respectively, of the Center for News Literacy at Stony Brook University.

- Jason Artman: Social studies department chair at Mendota Township (IL) High School and part of a team of teachers traveling the state to help colleagues implement new state requirements for the teaching of civics and media literacy.

- Sue Ellen Christian: Presidential Innovation Professor in Communication at Western Michigan University, former reporter for the Chicago Tribune, and author of “Everyday media literacy: an analog guide for your digital life.”

- J Scott Christianson: Professor at Mizzou’s Trulaske School of Business and tech entrepreneur.

- Shawn Healy: Senior director of policy and advocacy for iCivics, which advocates for equitable, non-partisan civic education in American schools.

- Philippa Hughes: Author, international speaker, and “social sculptor” who designs experiences aimed at bringing people together across cultural and political lines.

- Rep. Jim Murphy: State representative for District 94 in the Missouri House of Representatives and proponent of the “Show Me Digital Health Act,” which would require Missouri schools to teach responsible use of social media.

- John Silva: Senior director of professional learning at the News Literacy Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting news literacy by offering resources to educators and the public.

- Angela Scott and Lauren Williams: Adult and community services managers – and Seth Smith , public services librarian at the Daniel Boone Regional Library in Columbia. After attending the first Friends of the Facts conference in 2019, they won a state grant to create their own news literacy program, which was incubated at the Reynolds Journalism Institute.

- Julie Smith: Educational and media literacy consultant and author of “Master the Media: How teaching media literacy can save our plugged-in world.”

- Tara Susman-Peña and Matt Vanderwerff: Representatives of the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX), a nonprofit organization that works to expand access to quality education and information around the world.

- Dana Cassidy, Josh Schipper, Katey Williams and Kendall Porter: All finalists in the Reynolds Journalism Institute’s 2022 student innovation contest, which asked candidates to submit ideas for teaching media literacy.

Updated: July 12, 2022