Dean Mills: A Lifetime in Journalism, a Legacy as School of Journalism Dean

By Molly Duffy

Columbia Missourian

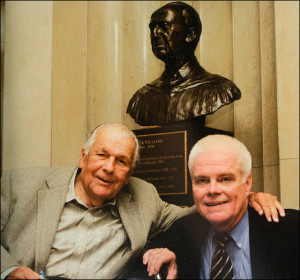

Columbia, Mo. (May 20, 2015) — In 2004, Dean Mills and Roger Gafke waited in the library of an office building in Las Vegas.

In a few minutes, they would walk the 50 feet to the Reynolds Foundation boardroom, where Mills, long-time dean of the Missouri School of Journalism, had only minutes to sell the dream he’d fostered for more than a decade.

He longed to build a center that would reinforce the principle of the First Amendment – a right given to citizens, not just journalists. Too often, the dean saw journalists claiming the First Amendment for themselves.

Mills believed that for democracy to thrive, both needed to work together. He envisioned a center that could explore the impact of new media technologies and act as a hub to propel journalism forward.

He had pitched the idea to colleagues when he was the coordinator of graduate study in communications at California State University, Fullerton, but the concept didn’t find financial support. After he became dean at Missouri, he found faculty enthusiastic about the idea.

Now Mills finally had the chance to pitch his dream to the board of the Reynolds Foundation, a group that could write a $31 million check and create the journalism institute.

Securing the Gift

In 1991, Gafke, then vice chancellor of development for MU and now emeritus journalism professor, had helped coordinate the foundation’s funding of the Reynolds Alumni Center with a $9 million gift – the largest donation in MU’s history at the time.

The gift was one of the last that Donald W. Reynolds, a 1927 MU graduate, was personally involved with before he died in 1993. Reynolds had been a journalism graduate, and Mills thought the foundation might someday give to the Missouri School of Journalism.

In Las Vegas that day, Mills was tense. The foundation had been encouraging but offered no guarantee. Summoned by a staff member, Mills and Gafke left the waiting room and walked down the hall to find some 15 people seated around a long, oval table.

A program officer waited to cut off the presentation if it ran too long. Mills would get a two-minute warning, just as he once did on the high school debate team.

The clock started. Mills began.

One minute in, the PowerPoint presentation crashed.

Mills was so focused he didn’t even notice. Gafke was “the cool one,” Mills said, who called out to stop him. But the glitch helped ease the tension – the board made a few jokes, and Mills laughed.

He started again, and when his time was up, he and Gafke walked back to the waiting room while the board deliberated.

Less than 10 minutes later, the board gave them an answer. The foundation’s gift became the largest in MU history and led to the creation of the Reynolds Journalism Institute. Seeing that dream come true, Mills said, was one of his most gratifying moments as dean.

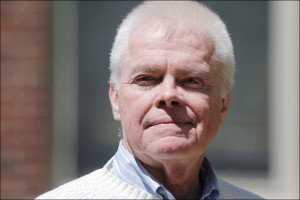

Mills presided over his last graduation ceremony on Saturday.

During his 26-year tenure as dean, Mills transformed the School of Journalism. He helped raise more than $200 million – seven times more money than all of the journalism deans before him combined.

In addition to the Reynolds Journalism Institute, those donations allowed for eight endowed chairs, the creation of Lee Hills Hall at Eighth and Elm streets and a number of faculty fellowships and student scholarships.

The money Mills secured helped the world’s first school of journalism maintain its status through a tumultuous era for the news industry. Under his leadership, the school has forged educational and journalistic partnerships around the world, nurtured a loyal alumni network, and diversified faculty and staff.

Thousands of journalists, strategic communicators and educators belong to the “Mizzou Mafia,” a loose collection of alumni with footholds in the industry and beyond. As much as anything, those alumni and the work they do is Mills’ legacy.

But don’t expect him to brag. Even as he prepares to retire, Mills maintains a deep aversion to talking about himself or calling attention to his accomplishments – or even using the word “legacy.” Those are the values he learned growing up as a Quaker in Iowa.

Iowa Born and Bred

Dean Mills grew up on a farm in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, the youngest of four boys. His father, Chester Mills, liked to pick apart what Quakers call “unthinkable transgressions.” And while Chester would occasionally boast about his own double play on the makeshift baseball diamond behind their farm’s field, his four sons were raised to believe bragging and lying were close cousins – a brag could easily become a lie.

Chester’s wife, Leora, never made it past the sixth grade, but no one intimidated her. A person’s stature didn’t matter; she embraced everyone. Chester would say Leora never met a stranger.

She had a beautiful, full laugh – a laugh she passed down to her youngest son – and she lived more effusively than her quieter husband. Chester had known at 13 that his place was on the family farm. He and Leora assumed that one of their sons would take it over some day.

It was fairly obvious that Dean would not be that son. He was a terrible farmer, and the list of his agricultural inadequacies grew as the years passed.

He overturned an entire load of hay while driving the tractor. He ran the harrow into a fence. For weeks, most of the hens’ eggs were inexplicably broken, so his father decided to investigate. He watched the 8-year-old crawl into the hen house, collect the eggs and then jump from the window – landing with a graceless thud.

Dean was never interested in farming. He fell in love with writing early, and by the time he was 10, he knew he wanted to be a journalist. He had heard they got to write and go places, and that was all he wanted.

When all of the Henry County eighth-graders submitted essays about soil conservation, Dean’s was nearly disqualified because one of the judges doubted the authenticity – she was particularly disturbed that he had used the word “lugubrious.”

He knew the word because he liked to spend time reading a dictionary to learn new words. It was his bragging loophole: Using a broad vocabulary allowed him to show off without technically boasting.

The school superintendent told the judge that he knew Dean and assured her those were his words. He won the contest.

High School Pals

In high school, he joined the debate team, sang in the choir, acted in school plays and musicals, and edited the school newspaper, the Maroon Echoes. He had a crush on Sue Cornick, but thought she was too pretty and popular for him.

They eventually went on a few dates (“She probably regarded them more as friendly outings,” Dean recalls, “but I regarded them as dates.”), and he convinced her to accept the features editor position at the paper before he graduated and left for the University of Iowa.

When Sue decided to transfer to the University of Iowa after her sophomore year at Drake University in Des Moines, she phoned Dean – he was the only person she knew in Iowa City. He answered, told her that he was writing an editorial on deadline and hung up on her.

Sue decided that was that and didn’t try to call again. A week later, she and the other girls in her rooming house were uptown for dinner, and Dean saw her on the street.

“Where have you been?” He called over. “I’ve been looking for you everywhere!”

Dean and Sue dated all through college. They would go to independent movies together, and sometimes Dean would read the Russian author Alexander Pushkin aloud to her in Russian (she didn’t understand any of it but still blushes and says she “thought that was pretty neat.”)

His mother would supply him with canned chili, and he’d turn it into something wonderful. “He was a stone soup kind of guy,” Sue remembered. Dean said he once asked her to make him a fried-egg sandwich, and she was baffled. “Oh,” he thought. “She really doesn’t cook.”

He was always busy. Editing the student paper, The Daily Iowan, consumed him. He spent the fall of 1964 studying at a historically black college in Talladega, Alabama. He wasn’t a campus protester, Sue said, but he had deep convictions about equality.

As a white student, he was a minority on campus in Talladega, and that changed the way he thought. The experience stayed with him.

“What he’s like now, he was then always doing things like that,” Sue said. “I’m not telling you he always knew precisely where he was going, but he knew he was going somewhere.”

Dean and Sue graduated together in 1965 and married the next day. Neither wanted a traditional Iowa wedding. Sue thought a fancy dress was a waste of money. She ended up wearing something pink, a color she scoffs at and has always hated.

One of Dean’s friends sang and another read poetry. Sue’s very pregnant best friend was her matron of honor. A Unitarian minister performed a Navajo ceremony, which celebrates individuality within a marriage.

Loves a Challenge

All deans are dictators, said Don Ranly, who began teaching at the Journalism School in 1974 and retired as the head of the magazine sequence in 2004. If you’re lucky, you’ll have a benevolent dictator – and that’s how he described Dean Mills.

“There’s no question that if he wanted something he got it,” Ranly said. “And that was almost always, in my mind, the right thing for the school.”

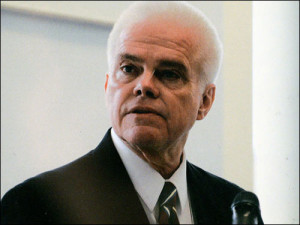

Mills loves a challenge. He said he’s served as dean for so long – longer than any Journalism School dean except founder Walter Williams – because the school never stopped presenting new challenges that “made it interesting all over again” for him.

“The man is an incredible visionary,” said Brian Brooks, who joined the faculty in 1974 and served as editor of the Columbia Missourian and associate dean of undergraduate studies.

“He’s done a lot of tremendous things,” Brooks said. “I have a real fondness for him and what he’s done here. Nobody in that position ever goes without criticism – there are people who didn’t always like his style.”

Some faculty members perceive a lack of full transparency. Daryl Moen, who also joined the faculty in 1974 and served as former managing editor of the Missourian and director of the news-editorial sequence, said Mills was open when he came to MU and conferred with a number of faculty before acting. Over the years, that group has gotten smaller, he said, and Mills no longer consults faculty before moving forward with an idea.

“I don’t always know what he’s thinking because he’s already four or five steps ahead of me,” said Lynda Kraxberger, who joined the faculty in 1993 and is now the associate dean for undergraduate studies. “That makes it interesting and challenging, but it also means that we’ve been in very good hands for the last 25 years.”

Journalism faculty have also noted that Mills can come off as unapproachable – his personality can be read as standoffish. He does his work quietly, and in doing so sometimes can cause rifts. When he fired Rhonda Fallon as the Journalism School’s fiscal officer after 21 years, she sued. They settled out of court.

Fallon said she believes office politics precipitated her firing. As the situation grew more toxic, she expected Mills to advocate on her behalf, she said, but he never did.

“Dean was a nice person – he was nice to your face – and he was charming, but you never felt like he had the best interest of staff in his view,” she said. “For faculty who created loyalty to him, he never reciprocated that. And if he did, there was a point where he didn’t.”

Mills declined to comment, saying he doesn’t publicly discuss personnel issues.

“He’s not a hail-fellow-well-met, he’s not a back slapper, he’s not out showing the flag,” Moen said. In the same way that Mills doesn’t brag about himself, he doesn’t brag about the Journalism School, either – many fault him for not publicizing the school’s accomplishments more often and more publicly.

But the sheer amount of time Mills has spent as dean speaks to the level of his success. College deans typically last seven or eight years, and Mills’ long tenure has allowed him to intimately shape the direction of the school. Although he isn’t often seen roaming the halls of the school, products of his labor are impossible to miss.

Industry History

When he finished his master’s degree at the University of Michigan in 1967, Mills fielded job offers from The Wall Street Journal‘s Chicago office, the Toledo Blade and The Baltimore Evening Sun.

Mills had heard about The Sun’s Moscow bureau, and he’d always dreamed of becoming a foreign correspondent. So he and Sue moved into a tiny garden apartment in Baltimore.

Mills didn’t realize that The Baltimore Evening Sun and The Baltimore Sun weren’t the same newspaper until one of his first days at work. He ran into a colleague who asked why he had chosen The Evening Sun, and Mills told him about his interest in the Moscow bureau. He looked at Mills like he’d lost his mind. The colleague explained that The Evening Sun didn’t even have a Washington bureau – and no one was sent abroad.

The two newspapers were owned by the same company but acted as fierce competitors. Mills had moved to Baltimore for the wrong paper.

He was embarrassed and disappointed, but two years later, The Baltimore Sun was looking for a reporter to send to Moscow. Mills, who is fluent in Russian, was hired. He was 27 and had never been abroad.

Mills, his wife and their 18-month-old son Jason moved to Moscow in 1969. It was the Brezhnev era, and the Soviet Union was under an authoritarian Communist regime.

Religious and political dissidents were beginning to contact the West through journalists. Mills began meeting people in the dead of night on isolated street corners. Many had been sent to labor camps, and often they were returned after speaking to him, Mills said. The experience was exciting, and he was too young to recognize the danger.

When Sue became pregnant with their second son, Jesse, she scoffed at the idea of flying to Finland to give birth, even though that was the common practice of Western mothers living in the Soviet Union. Babies are born every day in the country, she thought.

Shortly before the due date in August, Mills called the best hospital, only to learn that it had closed for the month. Their next choice had closed for renovations. So when the baby started coming, an ambulance took them to a hospital completely devoid of Westerners.

Men weren’t allowed inside, so they would stand outside the recovery room windows and throw pebbles to get the new mothers’ attention. Mills talked nurses into letting him inside to see Sue and the baby – and to write a story about the experience for The Sun.

Mills stayed in the Soviet Union for three years – one year longer than the typical stint – then moved to Washington, D.C., to work for The Sun until 1975. In 1976, he decided he wanted to shift into academia, but first he needed to earn a doctorate.

Academic Route

Mills worked on a doctoral degree at the University of Illinois for three years, until California State University, Fullerton, offered him a teaching position.

He finished the degree in 1981 while teaching in California. After two years in Fullerton, he applied to become the dean of the Journalism School at MU, but was passed over for James Atwater. Pennsylvania State University then asked him to direct its journalism program, and the family moved east.

Just after he arrived in State College, undergraduate Alecia Swasy gave him a tour of the Daily Collegian, Penn State’s student newspaper. Swasy’s father had recently died, so Mills became a mentor and a surrogate father for her, guiding her through her year as editor of the Collegian. He continued to coach her through the pressures of her reporting and editing jobs at The Wall Street Journal and The St. Petersburg Times.

Thirty-one years later, his is still one of the first numbers she dials with news.

“He looks like he was a former Marine, but nothing could be further from the truth,” she said. “He’s got a heart of gold.” Swasy earned a doctoral degree from the MU School of Journalism in December and now teaches at the University of Illinois.

Ultimately, Mills became dean of the School of Journalism at Penn State in 1985. He said he worked to extricate the journalism program from the College of Liberal Arts and make it a free-standing college.

Longing for the sun again, Mills moved back to Fullerton in 1986 as the coordinator of graduate study in communications.

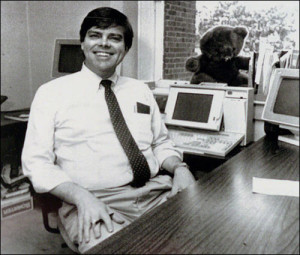

In 1989, MU was again looking for a dean. Learning that he was no longer at Pennsylvania State, the School of Journalism came calling.

His son Jason was finishing his degree at Washington University in St. Louis and moving to Philadelphia to do a Ph.D. M.D. at the University of Pennsylvania. Jesse was starting his freshman year at the University of California-Los Angeles. Dean and Sue Mills decided to move to Missouri.

Becoming Dean

Edmund Lambeth, an inside candidate, and Mills were the top candidates for the dean’s job at MU.

“It ripped this school apart,” said Steve Weinberg, the director of Investigative Reporters and Editors from 1983 to 1990 and author of “A Journalism of Humanity,” the history of the school that Mills commissioned for the school’s centennial in 2008.

Some faculty were convinced Lambeth, once the director of the University of Kentucky School of Journalism, and then associate dean for journalism graduate studies and research at MU, should have been hired. Others argued that the school needed new blood. Still others felt that, regardless of the outcome, the provost, Lois DeFleur, had made the hire without sufficient faculty input.

Ultimately, Mills was hired. When he became dean in June of 1989, the Missouri School of Journalism was still considered an old boys club. One of the first things he set about doing was diversifying the staff. During his first two years, he insisted on aggressively recruiting women and minorities.

Betty Winfield‘ was among the first wave of female tenure-track scholars Mills hired in 1990. That year, the chancellor, Haskell Monroe, invited the new hires to a dinner. Winfield, Mills and a few other new professors were all seated together.

In welcoming everyone, Monroe congratulated the new hires on their successes. Then, in an effort to acknowledge their spouses, he asked, “Would their sweethearts please rise?”

Wives of the professors at other tables stood up. Those at Winfield’s table froze – many of them were women. They looked at each other, then at Mills, and did their best not to laugh. Winfield said she remembers Mills staring at his shoes and doing all he could to keep a straight face.

“When he got here, I think it’s fair to say the school was not the happiest place,” Brooks said. “There had been a lot of problems with male-dominated faculty marginalizing women faculty.”

Winfield recalled being on a search committee for a new faculty hire sometime during the mid-1990s. After they made a decision, a male faculty member stood up, feigning shock.

“Oh my God,” he yelled excitedly. “We’re finally hiring a man!” The whole room roared with laughter.

Mills focused on appointing women with doctoral degrees to tenure-track positions. Among them was Esther Thorson, whom Mills hired as the associate dean for the graduate program in 1993.

Thorson set about fixing the criteria for journalistic academic research and opening the school to more faculty with doctoral degrees. Thorson said she always felt lifted by Mills; he never tried to tame her ambitions for the graduate program.

Missouri Method

The core of the Missouri School of Journalism has always been the notion of learning by doing – and that fueled its funding as much as it did the curriculum. In the early 1990s, it was safe to assume the industry would give philanthropically to journalism schools on a regular basis.

When rapid technological advances scrambled newsrooms a few years later, the Journalism School struggled, too. By 1995, just six years into Mills’ appointment as dean, the school needed to keep the curriculum relevant and develop new sources of funding to do so.

As the business model for journalism buckled, so did the school’s funding. The school’s news outlets – TV station KOMU/NBC, radio station KBIA/91.3 FM and the Columbia Missourian newspaper – were coping with the same issues as news business nationally.

“We had our face doused with reality every day,” Mills said.

A number of classes were exploring new technology, but there wasn’t much communication among them, Kraxberger said, which created redundancy in content. After an audit of the content, the Journalism School began offering a course of study in convergence – the first addition since introducing TV and radio in the 1970s.

Mills was also interested in widening the school’s international scope, both through study-abroad programs for students and through traveling opportunities for faculty. In 1994, he delegated those ambitions to an international office within the Journalism School. The Global Programs office today oversees study abroad programs around the world, including in Brussels, Buenos Aires, London and Barcelona. Fritz Cropp, who has run the office since 2001, said nearly one in three journalism undergraduates now studies abroad.

Looking Forward

Last year, Mills was invited back to Las Vegas. As the Reynolds Foundation prepares to close, its leadership was interested in giving a few of Donald W. Reynolds’ artifacts to a museum in the Reynolds Journalism Institute at MU.

Mills was told that the foundation wanted his opinion about the choice of pieces. He thought it was odd to fly to Las Vegas just to look at a few mementos, but he obliged.

The foundation had a surprise for him. The foundation had decided to give the school its residual funds – $10 million. It was up to Mills to decide how to use them.

As dean, Mills said he’s been particularly concerned about faculty salaries. Although starting salaries are competitive, long-time journalism professors at MU, on average, are paid less than professors at other public universities. That’s cost the school key faculty members, who have been lured to other schools by bigger paychecks.

Mills asked the Reynolds Foundation if the school could use the $10 million to endow 50 faculty fellowships for associate and full professors – and to allow the funds to be used, in $200,000 chunks, to match any $200,000 gift by another donor. The foundation said yes.

With the gift, the Reynolds Foundation will surpass the $100 million mark in donations to MU. If the $10 million works as he thinks it will, Mills said, the gift will ultimately endow 50 faculty positions at $400,000 each. Once the Reynolds Foundation releases all of those funds in 2021, it will cease to exist.

Retirement Plans

When Mills announced his retirement in February 2014, effective August that year, he planned to stay on campus to work as part-time director of the Reynolds Journalism Institute. But after spending a year longer as dean than he originally planned, he says now that he’ll “make a clean break of it.”

At 72, he said he’s ready for a traditional retirement and time with his family. His older son, Jason, is now an associate professor and runs a research lab at Washington University. Jesse has just taken a job with the UCLA medical school to direct a men’s health program.

Mills still loves a challenge, and cooking is one of them. Sometimes his wife will walk into the kitchen, and he’ll have strudel dough rolled across their white tile island. He has boiled bagels, made brioche, boned chickens – Sue Mills said she thinks he wants to make everything that would scare most casual cooks away.

During one of her last visits, Swasy noticed a book on the coffee table in the Mills’ living room. Swasy realized it was Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House in the Big Woods,” but the title was in Swedish. Mills was reading the book for fun.

In retirement, Mills said he also plans to finally read “War and Peace” in Russian and to revisit some of Pushkin’s original works. To him, there’s no better pleasure than reading a truly good work in its original form. Pushkin is like that, he said; too much is lost in the English translation. Maybe he’ll read more Pushkin to Sue, or his grandkids. After a career filled with challenges, Mills will likely find a new one. That’s the fun part.

Supervising editors are John Fennell and Jeanne Abbott.

Updated: September 8, 2020