In Niger, Missouri School of Journalism professors show journalists how to spot disinformation and tell compelling stories

Columbia, Mo. (Feb. 7, 2022) — Surrounded by a distinctive pattern of striped sub-Saharan vegetation known as “tiger bush,” Niamey, the capital city of Niger and the country’s largest city, is home to the Institut de Formation aux Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication (IFTIC), a school that trains students in journalism, video production, and other communication skills.

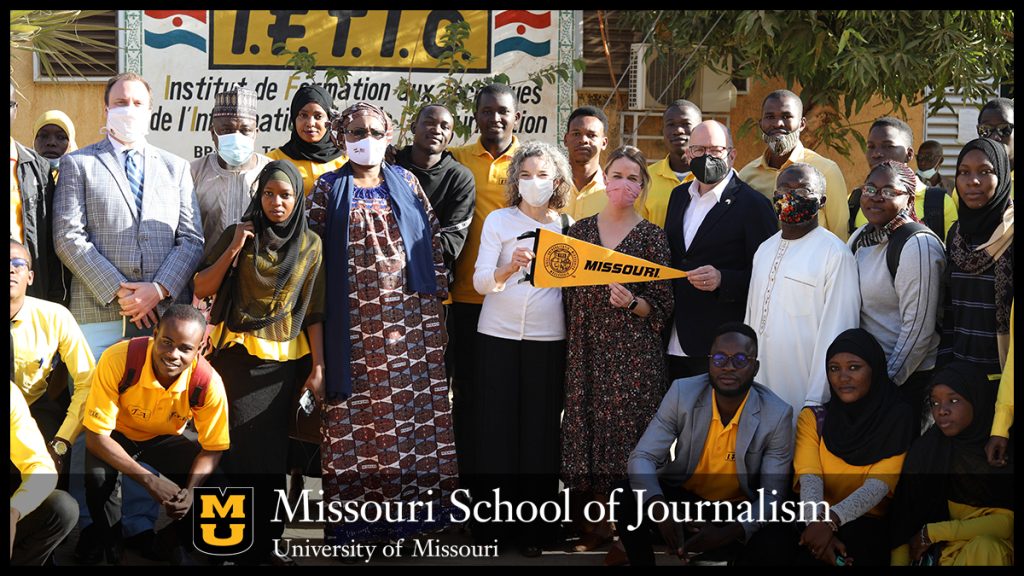

So when three Missouri School of Journalism professors arrived in Niamey to conduct a series of trainings for journalists from across Niger on a grant from the country’s U.S. Embassy, it was only natural that they would make a stop at IFTIC. They were greeted with another sight that made them feel at home: Students dressed in black and gold.

“When I told them that Mizzou’s colors were the same as theirs, the students just burst into applause,” said Kathy Kiely, a professor and the Lee Hills Chair in Free-Press Studies. “We came away with a whole new set of friends.”

Kiely and two colleagues she recruited to make the trip over winter break — professor emeritus Stacey Woelfel and assistant professor Kathryn Lucchesi — left a Mizzou pennant for the school, but their greatest impacts were farther-reaching. In Niamey and Maradi, the country’s second-largest city, the trio held training sessions designed to teach journalists how to identify and respond to disinformation, as well as teaching a broad set of multimedia skills and journalistic strategies.

A tense time for teaching

For two weeks in January, the series of two-day sessions drew journalists from each of Niger’s eight regions. They came at a time when Niger is facing terrorist threats on multiple fronts: from the southwestern tri-border region with Burkina Faso and Mali, an area that has seen a number of massacres fueled by ISIL and related insurgency groups, and from the southern border with Nigeria, which has seen rising violence from armed groups like Boko Haram. Disinformation through social media memes and other forms of propaganda can make discerning fact from fiction a full-time job for Niger’s journalists.

“The journalists who came to us were a little overwhelmed with how much they have to deal with, and they were looking for some help in terms of where to start,” Woelfel said.

To offer that guidance, Kiely felt it was important to not only explore the nature of disinformation, but to help journalists build their identities as truth-tellers by teaching broader skills. The instructors got the permission of Ron Kelley, an associate professor and executive director of student development, diversity, and inclusion at the School of Journalism, to adapt a series of MU’s online journalism training modules, and sought advice from assistant professor Monique Luisi, who wrote her dissertation about the impact of disinformation.

“We felt that the journalists would also want some training in technique,” Kiely said. “I saw it all as one piece. How do we as professional information providers distinguish ourselves from other people on the internet? It’s because we are better fact-checkers, better reporters, and better storytellers. So part of our training was about how to be better storytellers.”

In turn, the trio found themselves inspired by the journalists they spoke to. The media organizations they came across often took the commitment of serving the community to a level not often seen in the U.S.

“We encountered a community radio station whose most popular program involved checking out books from the library and reading them on the air,” Woelfel said. “They were doing news, of course, and talk radio, but they were sort of all things to all people, and they could be community leaders in a way that, frankly, we don’t see in the U.S. much anymore. You didn’t have to be literate or have a TV to listen. A transistor radio would do it. So they can reach a lot of people and be an important part of their communities.”

The human element

Despite the omnipresence of security personnel, Kiely, Woelfel, and Lucchesi still managed to find moments of connection to the people and culture of Niger.

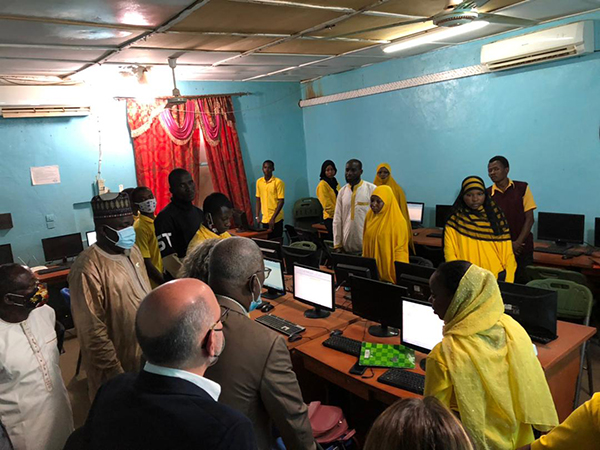

Woelfel recalled sitting in on pitch meetings in sparse and tiny local newsrooms, in which nearly a dozen journalists would share a single computer running dated software.

“For us, it felt exactly the same as in an American newsroom,” Woelfel said. “The tools are a lot fancier here, but it was a group of journalists sitting around a table, pitching ideas, trying to figure out what they were going to cover that day. It’s great how familiar that is regardless of the culture you’re in.”

Woelfel, who teaches the School of Journalism’s aerial journalism course, also found time to squeeze in the occasional hands-on drone demonstration.

For her part, Lucchesi — who lent her social media expertise to the project in a country where social media like Facebook and WhatsApp drive conversations about news and current events — relished a visit to Niamey’s English Club, where she was able to speak with a large turnout of English students about a wide range of topics.

“It was a fun experience because while they did want to know quite a bit about journalism, they also wanted to learn about the differences between Missouri and where they lived,” Lucchesi said. “We would find commonalities no matter what we talked about, and we just learned from each other.”

Appreciation of these human connections went both ways; at the end of one session in Maradi, a journalist stood up and thanked the trio for coming to Niger despite the security risks, an experience that highlighted for the trio how much the sessions were appreciated.

“It was very touching how much our presence meant to him, and he wasn’t the only one,” Kiely said. “I think it was really important for them to feel that there were other people in their profession who saw them and acknowledged what they were doing. Niger does not have a really strong democratic tradition, so to hear us talk about the importance of a free press was, I think, inspiring for everyone involved.”

Updated: February 8, 2022